This Web Page is: King Edward's School (Last revised 1/2/09)

Note: This page includes many

photographs which may take some time to load.

The following

narrative gives an account of my school days at K.E.S. in the 1950s – to the

best of my memory! It was originally

written for the benefit of our daughters, but subsequently expanded and a

version was serialized in the Old Edwardians’ Gazette in 2001-02. I am indebted to the late C.H.C. Blount and

to many Old Edwardians for comments and corrections. This is, of course, a personal memoir and

others may well have subtly different view of the years I describe!

Photographs © Robert Darlaston except where indicated

KING EDWARD’S SCHOOL

1951 – 1959

Robert Darlaston

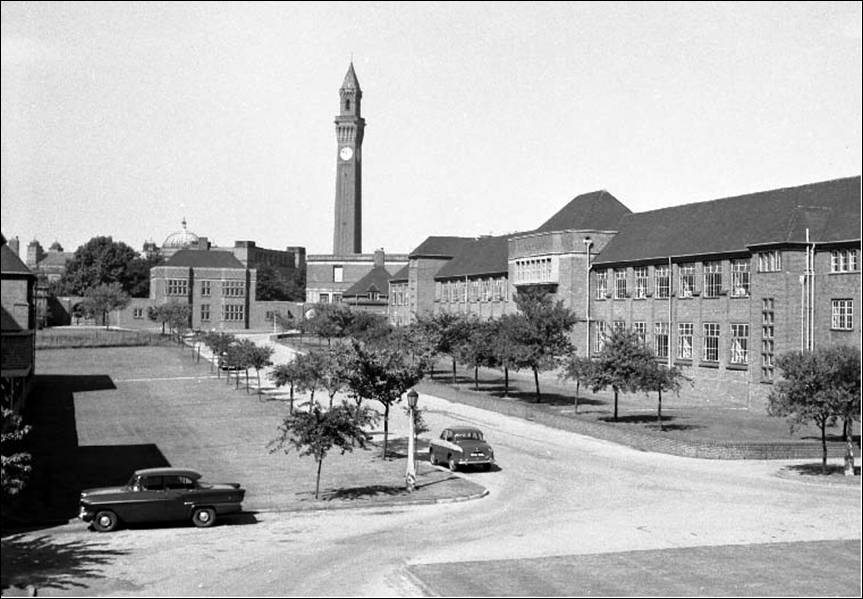

Looking up the Main

Drive from

= = i = =

|

I |

spent most of the 1950s at King Edward’s, - rather longer than

the majority of my contemporaries, as I had a second shot at ‘A’ levels. My stay thus spanned the years from the

Festival of Britain to the wonderful summer of 1959, one of the sunniest of the

century. It was a good decade in which

to grow up. My first few years had been

set in a world of bombs and rationing, where toys and sweets were almost as

scarce as penguins in the Sahara.

Austerity had continued after the war ended and, through the rest of the

1940s, life retained a dreary greyness aptly portrayed by the monochrome

newsreels of the period. But to a child

it seemed, superficially at least, that the arrival of the ‘fifties had brought

a fresh wind to blow away the horrors of the previous decade. Rationing was rapidly dismantled. Luxury goods began to appear in shops. Newspaper “hype” proclaimed a new Elizabethan

age. With Sir Winston Churchill as

Prime Minister, Everest newly climbed and the new Comet airliner briefly dominating the skies such claims for a while

appeared true. To a schoolboy it seemed

one was participating in real progress.

In that decade of full employment the motor car, television and the

foreign holiday became (for better or worse) a fact of everyday life. It was against that background that I spent

my time at K.E.S.. This narrative

gathers some recollections of those years.

My original aim was to give my children an insight into my own

schooldays, but the text might also provide some entertainment to other

contemporaries.

I started at King Edward’s School on 13th September

1951. I knew I was fortunate to secure

a place at a school which had provided education to the great and the good in

Birmingham for four hundred years and which was unquestionably one of the

finest academic establishments in the kingdom. Famous alumni of the twentieth century in

whose steps I was following included J.R.R. Tolkein, Viscount Slim, and the Rt

Hon Enoch Powell. Other pupils who

became household names for a time included a brace of bishops, the journalist

Godfrey Winn (a favourite in women’s magazines in the ‘fifties), comedy actors

Raymond Huntley and Richard Wattis, atomic spy Alan Nunn May and maverick drama

critic Kenneth Tynan (who was alleged to be the first person to use the ‘f***’

word on the B.B.C.).

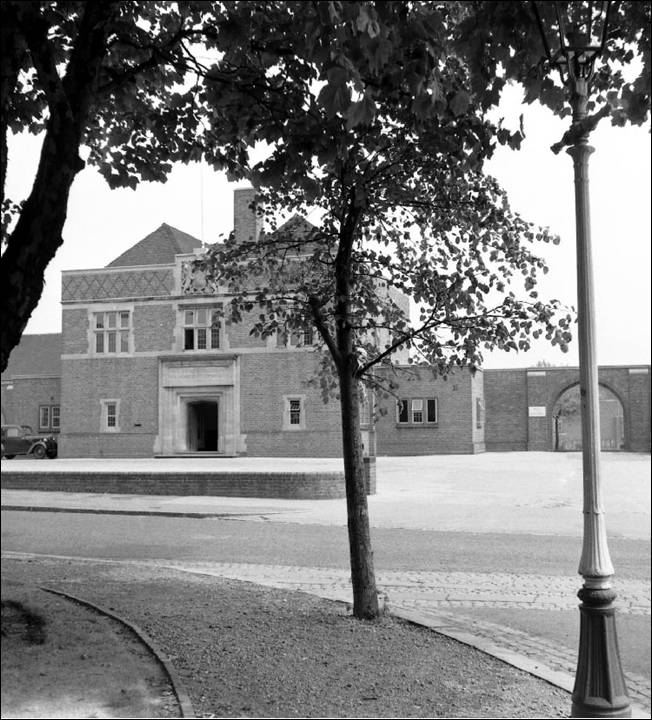

The school was a rich foundation which lacked for nothing and

had, only recently, moved from the bustle of the city centre to sumptuous new

premises in sylvan Edgbaston. The

facilities ranged from laboratories equipped to the latest standards to a small

cinema with tiered rows of blue plush tip-up seats. There were parquet-floored corridors, which,

to an eleven-year-old, seemed to stretch to infinity, and an assembly hall,

known traditionally as Big School, with a fine organ and one of the largest oak

hammer-beam roofs in England. The beams

for the roof had been delivered before the war and remained for the duration

lost amongst long grass and builders’ junk.

A government inspector had arrived to sequestrate them for the war

effort, but the site caretaker had denied any knowledge of them, and so they

had survived to provide the school with a magnificent setting for morning

prayers and formal occasions.

The contrast from my tiny previous school

could not have been greater. To a small

eleven-year-old somewhat lacking in self-confidence the sheer size was

bewildering and I duly got lost on my first day when searching for room

72. New boys were known as “Sherrings”

(a contraction of “Fresh Herrings”), which could occasionally be a term of mild

abuse when used by boys who had risen to the dignified height of the second

year. On arrival at K.E.S., I was

placed with 22 other boys in Shell ‘C’.

We were seated in alphabetical order and I teamed up with my neighbour,

whose surname was Cork. It was good to

have an ally in those early days, but Cork’s family were to move away after a few

years and he vanished from my modest circle:

the last I heard was that he made something of a name for himself in

Jazz circles! Our form master in Shell

‘C’ was Mr L.K.J. Cooke, a kindly man with a velvet toned voice and a leisurely

speech delivery. In consequence, unkind

schoolboys had nicknamed him “Slimy”, but he was an expert at easing new boys

into school life.

In accordance with tradition at boys’ schools we all called each

other by our surnames. (See

panel below). If two or more boys

shared the same surname they were known by their initials: in my year the Smiths were D.B., G.M., and

R.J., always known thus. Christian

names were regarded as “cissy” and kept top secret until any lasting

friendships were formed, usually in the later years of one’s school

career. Meanwhile, if, in the first

year or two, one’s Christian name was accidentally discovered by another boy it

might become a topic for fun. The only

boy in my day habitually known to his contemporaries by his Christian name had

the unusual name of

Modes of

address: “Call me Darlaston” Today the use of surnames is seen as curt and

unfriendly and first-name terms have become widespread—even with people one

has never met. But until the mid-sixties, surnames were the usual

form of address amongst males at school, in the Services and in the

professions. Christian names were

confined to family, a few close friends and, of course, girls (although

females in the services and professions such as nursing also used

surnames). For a boy starting at

secondary school being addressed by his surname was a badge of pride,

showing he was growing up: besides,

one was following time-honoured custom, as set out in novels about school

life from Tom Brown to Jennings

at School. To use a Christian

name was seen as over-familiar and disrespectful. Boys initially kept their Christian

names secret and, if discovered, unusual or old fashioned names such as

Harold or Cyril were a cause for teasing.

We called girls at the adjacent school by their Christian names, but

they would refer to us by our surnames (unless the relationship was

becoming close!) and when I went to a school friend's house for tea it

would be usual for his mother and sister just to call me Darlaston. Later, after starting work in banking, I found use

of surnames amongst staff was still customary into the mid-1960s. Memos to managers at other branches

would begin “Dear Jones”. Ladies

were, of course, always properly addressed by their title as Miss or Mrs X,

a custom which has sadly been neglected in newspaper usage in recent times.

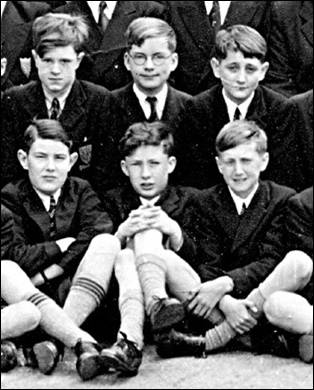

Back (l-r)

Sessions, Edwards,

Mitchell

Front (l-r) Birch, Darlaston, Robertson

Caps and navy blue blazers were the main element of uniform

throughout the School. There seemed to

be an unwritten rule that until boys entered the Upper Middle in their third

year short trousers were worn, shirts were grey, and raincoats were navy blue. Thereafter, one graduated to the dignity of

long trousers, white shirts and fawn raincoats. Similarly, the satchels of the first two

years suddenly became quite passé and were replaced by smart leather brief

cases in which to carry one’s ‘prep’.

For some boys, brief cases gave way in turn to C.C.F. packs or duffel

bags which were popular towards the end of the ‘fifties. In my first year at K.E.S. sixth formers

were permitted to wear sports jackets with flannel trousers and to leave off

the school cap. This gave them, in the

eyes of boys in the ‘Shells’, a somewhat awesome appearance whereby they were

difficult to distinguish from young masters.

That sanction was withdrawn in 1952 when caps and blazers became

required wear throughout the school – a rather unpopular change in the sixth

form as it diminished their apparent majesty.

School continued until 3.45 p.m.

only on Mondays and Wednesdays. On

other days lessons finished at lunch time, but that did not mean one could go

home. There were compulsory games for the first three years and these could be

on Tuesday or Thursday afternoon.

Friday afternoons were reserved for cadet force and scout group

activities, with non-participants being labelled “Remnants” and consigned to

the Art Room where Mr J.Bruce Hurn presided.

There was also morning school on Saturdays. The school was a single sex establishment,

but there was an adjacent girls’ school (K.E.H.S.). The authorities required that there should

be no mixing between the boys and the girls, and the starting and finishing

times were staggered by 15 minutes to discourage the evils of fraternisation on

the trams and ‘buses. Unsurprisingly,

this policy was not entirely successful.

During my own early journeys across the city to school a fifth-former,

Stevens, who later went into the medical profession, kept a friendly eye on me,

aided by a couple of Upper Middle boys, Davis and Allen, and there were also

two girls from K.E.H.S., Ann and Margaret, who initially tried to mother me: (Christian names for the girls, but surnames

for the boys in those days, be it noted!).

On Friday morning journeys in that first year, Darlaston’s Eagle comic was enthusiastically

borrowed by the rest of the party – especially the girls - so that everyone

could keep up to date with the adventures of Dan Dare, Pilot of the

Future. [See illustration in the “Memory Lane” page]

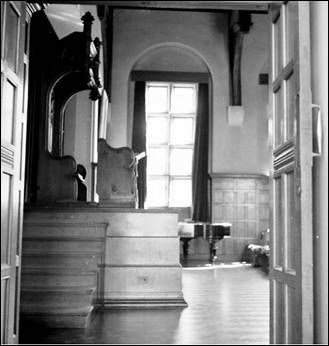

Classical corridor, looking towards

Big School. Upper Corridor:

At my junior school I had always been

a relatively big fish in a very small pond and was usually top or second in the

class. At K.E.S., by contrast, I was to

be in the company of some very bright pupils and consequently seldom rose above

the bottom third. At least I usually

enjoyed subjects such as English, History and Geography. But Mathematics was a real struggle. When I was about thirteen, the Maths master,

Mr Skinner, was explaining to the form some recondite algebraic formula which

was taxing my limited faculties. My

face clearly betrayed my total and utter bewilderment. Suddenly he broke off in mid-sentence and

said: “Darlaston, when you look at me like that, you make me feel an absolute

cad!” I confess to remembering that

incident better than any of the algebra he struggled to impart.

One of the most significant changes I found

on starting at K.E.S. was compulsory participation in games. I was allocated to Mr Leeds’s house, later

known as Jeune house, to commemorate a 19th century master. I fear my contribution to the house was to

be negligible, although Mr Leeds was surprisingly kind to me. At my previous school classes comprised

about a dozen children, of whom the majority were girls, so organised games

such as football and cricket had been non-existent. Moreover, there were no boys of my own age

living very close to home.

Consequently, as a somewhat timid only child I grew up to be rather

self-sufficient and quite ignorant about team games. K.E.S. attempted to teach me the rudiments

of Rugby football, but wrongly assumed I had some existing knowledge. This became all too evident in one of my

early attempts at Rugby when the master acting as referee (Mr J.F. Benett)

shouted at me “You are off side”. I

hadn’t the nerve to tell him that I did not have the slightest idea what he

meant, and I never did get the hang of it.

My self-sufficient approach to leisure together with my lack of

confidence in my own ability contributed to an absence of any competitive

spirit when it came to games. I failed

to see the point of running round chasing an oval ball, getting covered in

mud. The mud meant that games, like the

weekly gym lessons, concluded with showers.

I soon overcame the affront to the modesty I had cultivated as an only

child and cheerfully mingled with the crowd of boys who emerged from the steam

looking like a shoal of slippery pink prawns.

Although I happily accepted the showers, I did draw the line at sharing

the (off-) white tiled bath at the Eastern Road pavilion with its thick muddy

water, heavily occupied by fifteen or more adolescent sportsmen celebrating (or

lamenting) their performance on the rugger pitch.

Left:

the South Front during

break: the Chapel is in the distance

Right:

the view

down Park Vale drive from the East Door.

The

At the time I started at K.E.S. the

Headmaster was Mr T.E.B. Howarth. I

only had one encounter with him. He was

showing some guests around as the bell went for the end of school at 3.45 p.m. My form made a rush for the door and the

leaders became momentarily wedged there until pressure from behind caused them

to burst in a heap onto the corridor floor at the feet of Howarth and his

guests. He looked down at the eel-like

writhing pile of pupils and with exaggerated bonhomie said “Little

horrors!” Had there been no guests

present I feel that his comments would have been decidedly sharper and

detentions might have been mentioned.

Detentions, it should be added, could be awarded by Prefects and by

Masters. The former involved standing

to attention from 4 p.m. to about 4.45 and were usually punishment for such

misdemeanours as running in the corridor or (my own speciality) talking in Big

School before prayers. Master’s

Detentions were infinitely more serious and kept one in school for the whole of

Saturday afternoon. Happily, my

Saturdays remained free from such interruption throughout my school career,

although it was a close run thing once or twice.

Howarth left the school in April

1952, moving on successively to Winchester, St. Pauls, and Magdalene College,

besides making a career as a writer.

His successor, Canon R.G. Lunt, was an Old Etonian, who was to remain in

office for 22 years until his retirement.

Lunt was not generally popular, either with staff or pupils – he would

not have seen popularity as any part of his function. He was widely viewed as an unrepentant

snob; he was autocratic in an era of

rising democracy; and he embraced

earnestly the classics and arts, while showing less obvious interest in the

developing world of science. But he

significantly raised the profile of the school in the city, helped, one must

add, by the presence of H.M. the Queen who paid a brief visit one wet day in

1955 belatedly to commemorate the school’s 400th anniversary.

In the 1950s Lunt taught Classics to Sixth Formers, Divinity to

some forms in the middle school and English once a week to boys in their first

year. This showed a commendable concern

to see that nobody could regard him as a faceless administrator. I encountered him in the course of English

lessons as an eleven year old – “one of the toddlers” to use his own somewhat

damning phrase. I prided myself that I

did not have a dreadful Birmingham accent, but my enunciation was clearly not

up to the standards of Lunt’s Etonian and Oxonian delivery. In reading from “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” I referred to ‘Mustard-seed’, pronounced

as spelt. I was directed to spend the

weekend saying over and over again “I MOSST

remember to say MOSSTard-seed”. He would himself sometimes mimic the

Birmingham accent by warning that if you broke his rules “Yer will find yerself

gowin’ up the drive fer the last time”.

He certainly presented a commanding figure in

Big

School from the stage showing the organ Sapientia from the side entrance to Big School

A fine example of the

Lunt approach to school life was his ceremonial creation of prefects. After morning assembly, he would summon boys

so honoured up to his presence in Sapientia. He would take the appointee’s right hand in

his and then intone the prefect’s name in full:

“Gerald Aloysius Fothergill”, or suchlike, – and seventy impertinent

Upper Middles would think “Gosh! Who’d

have guessed Fothergill was called Gerald

Aloysius of all things” – while Lunt continued: “I, twenty-fifth Chief Master of King

Edward’s School, hereby give unto you the position and traditional

powers of a prefect, entrusting to you a share of the leadership and

governance of the boys brought up in this place: see that yer wield this power with justice, loyalty and discretion.” Those

three nouns resounded with truly frightening emphasis around

One of Lunt’s more endearing eccentricities was his attachment

to a Rolls Royce motor car, dating from the 1920s. He doubtless felt that it was the only make

of car appropriate to one of his standing.

He always drove it to school, perhaps a half mile by road, despite

having a private path about 200 yards long from his house to the school. Vintage cars are not always reliable. On one occasion the Rolls broke down while

delivering a guest speaker from the station to the school, no doubt a cause of

considerable embarrassment. Sadly, the

Rolls was soon to reach the end of its career, as during a severe frost its

cylinder block fractured and it had to be ‘put down’. Thereafter, Lunt was reduced to motoring in

more proletarian vehicles. [See note below the next photograph for

further information about Canon Lunt]

His unashamedly elitist attitude

enriched the school in a variety of minor ways, as “old traditions” were

re-discovered – or invented, as some cynics would have it. He invoked a little known reference from

past years to insist that instead of being called Headmaster, he should be

known as “Chief Master” – after all, St Pauls had a High Master. Various areas of the school were given

names: the courtyard where the naval

cadets practised became Admiralty Yard, that adjacent to the Music Room became

Chantry Court. A small group of

conifers was named Prefects’ Grove, although I doubt if that indicated any

requirement for gardening activity by the eponymous gentlemen. In summer boys were encouraged, but not

compelled, to wear boaters. I duly

complied and found it fun overhearing the comments – not always entirely

complimentary – passed by other passengers on the ‘bus as it made its way

through the less well-heeled districts of Birmingham. One elderly gentleman came up to me in

Corporation Street to congratulate me on my turn out and insisted on shaking my

hand. That was an occasion when I was

also wearing a rose in my button-hole:

by no means an unknown practice in the 1950s amongst professional men

and, curiously, railway guards in rural areas.

My second year was spent in Remove C

where the Form Master was Mr J.D. Copland. He cultivated an eccentricity of behaviour

which was often quite extreme and resulted in him earning the nickname “Coco”,

after the popular clown of the day. He

muttered to himself as he walked down the corridor, and was quite liable to

stop abruptly, cry out loud: “Ha!”, wrap

his gown tightly round himself like an Egyptian mummy, turn round and walk back

whence he came. A deaf aid added to the

impression of eccentricity, as, when bored by a boy’s long-drawn out and

inaccurate explanation of a point, he would fiddle with the volume control,

causing high pitched screeching sounds.

On snowy winter days he would wear Wellington Boots in which he would

squelch audibly and happily along the corridors. The unconventional behaviour masked a sharp

mind and a sympathetic interest in the boys in his form which only became

apparent after the passage of time. His

main punishment weapon was gentle humiliation.

If one dared to talk to a neighbour in a lesson, Copland would interrupt

his own sentence: “Darlaston; how dare you talk while I am speaking? Stand on the desk, boy.” As one self-consciously climbed up on the

desk, watched by all the form, he would wait until one was almost in position

and then say: “What are you doing up there boy? You look stupid – get down at once.” This always provoked laughter amongst the

rest of the class. An alternative

punishment sometimes hurled at one was “Write out the first 500 lines of The Revenge.” Later, he would suddenly turn to the

offender and say: “Make it the first 200 lines”, and later still “make it the

first 50 lines.” One might end up only

doing the first ten lines. If he

thought one was getting too familiar with The

Revenge, Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner

might be substituted.

When marking essays from junior boys

Copland was quite kind, and I usually scored 15 to 18 out of 20. But he also taught ‘A’ level History, where

the demands were far more rigorous, with a requirement to discuss and analyse a

topic, rather than to give mere description.

My first such attempt was not up to scratch. As he handed out each boy’s essay, he would

comment briefly. When he reached me he

lingered on the mark as if to emphasise the enormity of my failure, before

adding some very back-handed encouragement:

“Darlaston – two-o-o-o, out of twenty:

but don’t despair, boy, you will find it easy to improve. A fifty per cent improvement will take you

to three out of twenty, and a one hundred percent improvement will take you to

four." This was something of a blow

to my limited self-confidence, but I struggled up to eight or nine with

subsequent essays which was, from him, quite a healthy mark! [See

note below the photograph for further information about Mr J.D. Copland]

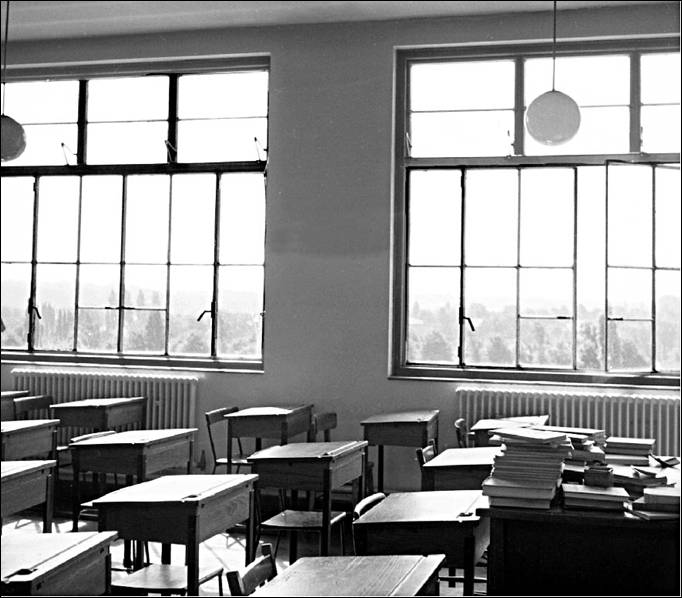

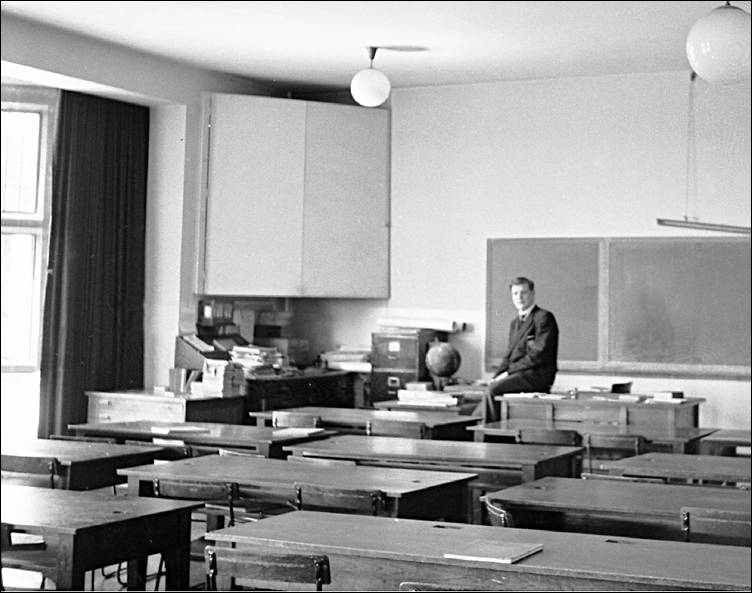

Room 149: Mr J.D.

Copland’s room and my form room in Remove C and History Division.

In both years I sat by the radiator at the left: very comforting in winter. Beyond lies sylvan Edgbaston!

Note:

I was most interested to

receive an e-mail from Mr D.D. Griffiths who is a nephew of Mr J.D. Copland. He writes:

“James Denison Copland was my Uncle, my

Mother's youngest brother, and I find your description of his behaviour most

accurate. He did not marry until late

in life and used to stay with my Grandmother in

He also liked to get my sister

and me to run round the block with him timing us with a stop watch.

He would sometimes ask my Mother

to carry out running repairs on his gown, which was so old that it had an

almost green tinge to it. The sleeves would be torn and much shortened by

catching on desks.

After my Grandmother had died

Uncle Denny (as he was known) used to stay with us. He was a very early riser and it was not

unusual for him to shout upstairs at 6 am, "I'm off, see you next

Wednesday". This was followed by

an earth shattering slamming of the front door. On his return we would get a loud

explanation as to where he had been, such as, "Went to

I could go on at length, however,

when I was older I found him very good company, especially in the pub!

“I was at

The "new traditions"

which you mention are almost exact replicas of ones which he instigated at the

College. The words for the initiation

of prefects only varied in that it began, "I, tenth Principal of this

College......"

One of his favourite forms of

address to a boy was, "You loathsome creature, what would yer father

say?"

I remember him getting the Rolls

Royce; it was left to him by his father

who had been the Bishop of Salisbury. I

particularly remember him coming to the school Scout camp in

“After Ronnie had gone to

It is fascinating to have the veil briefly lifted on the private life of

a master who was then so difficult for us to fathom!

= = ii =

=

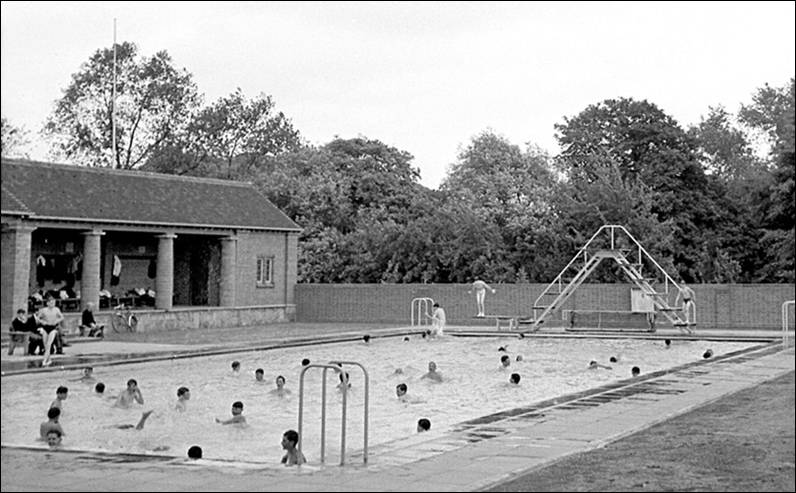

1952 was the year of the school’s 400th

anniversary. It was commemorated by the

opening of the chapel, with adjacent outdoor swimming pool, as a memorial to

boys who had been killed in the two world wars. The chapel was a fine reconstruction, using

the original stone, of the splendid gothic upper corridor from the former

school building in New Street. It had

been designed by Charles Barry (architect of the Houses of Parliament) but had

been demolished in 1936, making way for shops, offices and the cultural

delights of the Odeon cinema. The

memorial Chapel was to be used for early morning Holy Communion and for

Evensong after school on Fridays.

Services were normally conducted by the Chaplain, the Rev. F.J.

Williams, who taught Classics and was generally known to his pupils as

“Stuffer”. There was something

especially atmospheric about attending Evensong at dusk in the late autumn

months, as mist gathered over the nearby playing fields. The voluntary early Communion service was

followed by a splendid cooked breakfast in the Dining Hall. Often there was a guest celebrant, which is

how I once came to spend breakfast chatting with the Bishop of Birmingham!

The Chapel, seen across the Parade

Ground, with the pool beyond Chapel

Interior

The swimming pool, which was adjacent to the Chapel, had attractive

sandstone cloisters for changing, but was unheated in its early years and thus

had relatively little use. I wanted to

learn to swim, but, because of my general lack of self-confidence and the short

time available each year for lessons, even when I reached the Sixth Form I had

still not succeeded. We were only

allowed in if the water temperature reached 63°F, when swimming would

take the place of gym periods. Even in

June, a cold night might knock the temperature down below 63°. Conversely, one sometimes found that

swimming had unexpectedly replaced a gym lesson after a couple of mild days in

May. Lack of swimming trunks was no bar

to participation on such occasions, or, indeed, at other times such as a sunny

lunch-hour when an impromptu dip could be rather pleasant. Many boys equate excessive modesty with

vanity and so one participated happily on those occasions, unconcerned whether

outsiders might be looking over the wall.

A Summer’s lunch hour at the Swimming Pool.

The boy on the spring board is one of

several present who did not let lack of suitable attire prevent him from

enjoying a cooling dip.

The next year took me to the Upper Middle

with F.L. “Freddie” Kay as form-master, followed by a year in the Fifth form

with A.J. “Gozzo” Gosling. “Freddie”,

who taught English and History, was unlike the general run of schoolmasters at

K.E.S. He was short and ebullient to

the point of chirpiness. He was also a

keen motor-cyclist and would arrive at school heavily disguised in black

leathers with goggles, looking more like a despatch rider from El Alamein. “Gozzo” was, by contrast elegant and laconic

with a neat but sarcastic turn of phrase.

One of his lessons was interrupted by a practical joke which

misfired. Two boys, Payne and Rogers,

had rigged up a device with a ruler, elastic and string, which they meant to go

off, making a rat-tat-tat noise inside a desk, after the lesson had finished. Unfortunately it went off unaided while

“Gozzo” was in full flow. He stopped, tapping his fingers while the noise

continued, his face growing steadily more flushed. When the noise eventually ceased he barked

that the whole form would be in detention the following Saturday, but the perpetrators

owned up and the rest of us escaped. [Addendum: since writing

the above, S.P. Tyrer, one of twins in our year, has claimed responsibility for

this modest outrage. I trust it is not

libellous to say that it would not have been entirely out of character for

Payne and Rogers!]

There were other masters encountered

through these first four or five years, many of whom are easily remembered for

individual characteristics. G.C. Sacret

(“Sacco”) taught Latin to younger boys.

A big man, he had easily the loudest voice in the school, heard to best

effect across the South Field on a summer’s afternoon when the windows were

open. He had memorable ways of

emphasising points of Latin grammar. “A

gerun-dive is an adjec-tive which takes the subjunc-tive”; “didicissem? – iubet” (“did ‘e kiss ‘em? –

you bet” - though what that was supposed to illustrate I cannot remember). “Sacco” was generally of a cheerful and

sunny disposition and a splendid teacher for small boys, but if he were in a

bad mood he would draw a flagpole up the side of his blackboard with a red flag

at the top. This warned that anyone

who larked about did so at his peril.

As a housemaster, his stentorian voice was used to good effect on the

touchline to support the house team. An

early initiative by “Sacco” to encourage new boys to take an interest in their

surroundings was “hunt the motto”. Some

areas of the school had large skylights, incorporating latin mottoes in a

pattern around the border. Sixpence

(2½p) was offered to the boy who could find Mens

sano in corpore sano (a healthy mind in a healthy body). No one could, for that motto was very high

up in the skylight over the steps down to, appropriately, the Gym.

Latin was also taught by Tom

Freeman, known, presumably for alliterative reasons, as “Ferdy”. My encounter with him was during the time

when the Cartland Room was being built above the Classical corridor. The construction work involved a rope and

pulley system outside his window for hauling up building materials. To a bunch of fourteen-year-olds this was

inevitably of more interest than Caesar’s exploits in Gaul. “Ferdy” stopped the lesson and made us all

face left and solemnly watch the bucket going up and down for five minutes

until we were so bored with it we were glad to return to our copies of Latin for Today, the covers of which

were often so cleverly amended to Eatin’

Pork Today.

“Spike” Jackson was a charming and

kindly man, who took Holy Orders on retirement.

He was, however, sadly incapable of maintaining discipline in class and

his maths lessons could be turned into a shambles by a determined form of

troublemakers. On one occasion he

arrived to take a lesson to find that all the desks had been turned to face the

wrong way. By contrast, Mr W. Traynor

(Physics) tolerated no trouble. A small

man with gingerish hair, he gained the nickname “Cocky”. As Flight Lieutenant he led the R.A.F.

section of the cadet force. They

possessed a curious manned glider kit which could be assembled and, in theory,

launched for a few yards of flight from a kind of catapult which seemed to rely

mainly on elastic and brute force. In

practice it seldom left the ground, but on one occasion the school magazine

reported that the Officer Commanding had succeeded in getting a few feet off

the ground. The report added “He should

not get too cocky over this flight in

the trainer.” This was then thought to be quite daring.

The CCF Glider on the South Field in

March 1957

The Temporary Buildings, used while

the new school was under construction, are at the right

Other members of the Science Department

whom I encountered were Mr S.D. “Slasher” Woods and Dr R.S. Allison. “Doc” Allison was a forthright Lancastrian

who once caught me pouring a small quantity of acid into a test tube without

having first measured it. “Dorn’t joost

lob it in laddie” he shouted at me. The

chemistry laboratory was the scene of my greatest inadvertent attempt at

mayhem. I lit a Bunsen burner with a

spill of paper, threw the paper away and walked to the balance room down the

corridor to weigh some chemicals. When

I returned three minutes later everyone was running round in chaos, the air was

thick with smoke and all the windows were all open. My spill of paper had not been completely

extinguished and had set fire to the contents of the waste bin to quite

spectacular effect! I succeeded in

having accepted my plea of not guilty to attempted arson.

In the Upper Fifth, my year for

taking ‘O’ levels, my form master was T.R. Parry, a rugby playing Welshman who

taught English. He had a strong

personality and knew how to handle rebellious boys in their mid-teens. There was a fine team of masters teaching

Modern Languages, but this was a department of the school I did not experience

in depth. “Jack” Hodges was the patient

and helpful master who ensured that I developed a basic understanding of

French.

The teaching staff was all male, but

there were three females on the premises.

Miss Chaffer was the long-serving chatelaine of the kitchens, and there

were two secretaries, of whom Miss Minshull was the senior. For a short time there was an extremely

attractive assistant secretary called Wendy.

She was about nineteen and was immediately appropriated by Wilkins, the

deputy School Captain, who thus became an object of great envy by the rest of

the older boys. It was hardly

surprising that Wendy did not remain long at K.E.S.: the pressures on her from Wilkins and his

rivals must have been enormous! It

would have been about the same time that I was sweet on a rather pretty girl

from the adjacent school. Even though I

occasionally sat next to her on the ‘bus and spoke to her from time to time, I

was far too shy to mention such matters and she presumably remained forever

ignorant of my brief infatuation. It

was often said by opponents of single-sex schools that they encouraged

unnatural relationships between boys. I

recall no evidence in my day of any serious examples of such activity, although

there were occasional superficial and unsophisticated associations between

individual boys, discovering new delights as they grew to maturity! There was, of course, no formal sex

education in those innocent days and boys acquired an often garbled knowledge

of the subject from their contemporaries.

I initially held out against believing the information I gained in this

way as the procedures in question then seemed utterly bizarre and quite

absurd. One of my classmates who

clearly had a bright future in business acquired a pin-up magazine with some

discreetly posed black and white photographs of unclothed females, which he

hired to his fellows at two pence a go.

He did a brisk trade but I failed to take up the offer, whether through

prudery or because I feared a maternal audit of my pocket money expenditure I

cannot now recall. But in the chaste

atmosphere of the 1950s such distractions were little more than a passing fad

to naïve fourteen-year-old boys who found sport or such popular hobbies as philately,

train-spotting or ornithology offered greater fulfilment in their everyday

lives.

Music was a feature of importance at the

school, but with what would now be regarded as an elitist approach. The Director of Music was Dr Willis Grant

who later left to become Professor of Music at Bristol University. He was principally interested in Church

Music and extracted phenomenally high standards from the Choir. He was supported in my time by one of my

Sixth Form contemporaries, J.W. Jordan, who became an Organ Scholar at

Cambridge and was to be Director of Music at Chelmsford Cathedral while still

in his twenties. Jordan was a truly

remarkable organist, accompanying morning prayers on most days. He could extemporise freely and on the

morning in 1957 that Sibelius’s death was announced his voluntary was a set of

improvisations on Finlandia. Another musical contemporary was David

Munrow who became a performer and broadcaster of considerable note before his

tragic early suicide.

My own contact with Willis Grant and his

Music Department was negligible apart from the weekly school hymn practice

sessions, although he did once tell me to stop whistling in the corridor: it was, he quite correctly remarked,

“antisocial”. He showed relatively

little obvious enthusiasm for music beyond his specialist field, and displayed

a strong disapproval of any form of popular music. There were, however, occasional concerts

named after Julian Horner who had evidently bequeathed money to promote music

at the school. From time to time

afternoon school would be suspended and everyone directed to Big School for a

concert provided by an ensemble of “semi-professionals”. I enjoyed music but have to admit that the

baroque ensembles which seemed to provide the usual fare at Julian Horner

concerts did little to encourage my interest.

There was, however, one occasion when a group of singers, with piano

accompaniment, came to give a “potted” version of a Mozart opera. Excerpts would be sung and then one of the

characters, in costume, would come in front of the curtain to set the scene for

the next excerpt. But on one occasion,

after explaining what was to come, he could not find the gap in the curtain to

return to the stage. He chased

backwards and forwards in mounting panic, tugging vainly at the curtain to find

the gap. Clad in 18th

century wig, jacket and breeches, the poor man looked increasingly absurd as he

darted to and fro while his neck became redder and redder. Titters began in the audience and before many

seconds had passed the entire school was paralysed with laughter. Even the masters joined in. Eventually, he found the gap and retreated

to loud cheers. At the next break he

prudently held the edge of the curtain to ensure safe passage after his speech,

and he departed to great applause.

Until I was about fourteen my

knowledge of classical music was negligible and confined mainly to a handful of

pieces used as incidental music on wireless or television. The impetus to broaden my knowledge came one

sunny Friday afternoon in May 1954, a few weeks before my 14th

birthday. It was half term weekend and

school had finished at lunchtime. Most

boys had gone home but I had arranged to meet my parents in the centre of

Birmingham late in the afternoon before driving to South Wales for the

weekend. To while away the time, I sat

reading in the sunshine on the South Field.

In school, another boy who had remained behind was practising the piano

and the sound was drifting through the open windows into the warm spring

air. He was a competent player, but

repeated the same magical theme several times.

I had no idea what it was but soon learned that it was the piano part of

the first movement of Grieg’s Piano Concerto.

I could understand why it was one of the most popular works in the

repertoire. This encouraged me to

listen to broadcast concerts where I was to discover a world of endless delight

and fascination. I also found that

several of my friends had a similar embryonic interest in music and this led to

interesting discussions during our leisure time which, in turn, developed one’s

interest still further.

South Field from the Library 1959:

stone-picking in progress on new rugby pitches.

Chapel at left

Pop music, as known today, did not exist in

the early 1950s and so it was not difficult for Willis Grant to maintain the

purity of classical music in the school.

In pop terms, neither the market nor the product existed. Things began to change later in the decade,

especially under the influence of Bill Haley’s “Rock around the Clock”. Cliff Richard arrived on the scene and a

phenomenon called ‘skiffle’ was introduced.

By now Willis Grant had moved on and his successor, Thomas Tunnard,

recognised that a more flexible attitude was appropriate. For a while a ‘skiffle group’ was

established in break, performing in the tuck shop. It was all very low-key by the standards of

later decades, but made a musical change from the break-time practice of the

cadet force band who only knew one tune, endlessly repeated over the

years. The skiffle era coincided with

the rising popularity of the Espresso Bar.

One such establishment was El

Sombrero in Bristol Street. It was

popular with a group of rather maverick boys who could be found there on

half-days, capless and smoking cigarettes.

Eventually, the Bar was placed out of bounds by Lunt. Another place which neither boys nor staff

were expected to patronise was the Gun Barrels public house on Bristol

Road. There is an apocryphal story that

a boy and a master met in the Gun Barrels on one occasion. Each is reputed to have said to the

other: “If you don’t split on me, I

won’t split on you.” Further up Bristol

Street from El Sombrero, on the

opposite side of the Horse Fair, was another

The school tuck shop was run by

Allard, the Head Porter. His

predecessor, Kelly, had ruled the shop in the days of sweet rationing. The only ‘sweets’ not on the ration when I

started at K.E.S. were very strong ‘Troach’ cough sweets to which I became

slightly addicted until rationing of other delights was ended. Sweets were loose in those days and paper

bags very insubstantial. Thus my mother

regularly found in my blazer pockets a solid wedge of sticky sweets, all

covered in navy blue fluff, the paper bag having disintegrated long ago. Allard was a former policeman of substantial

build and conducted himself accordingly.

His chief assistant was Cradock, a bluff individual with a sharp sense

of humour, essential in his job. He had

an artificial leg, which gave him a characteristic gait, as he hurried on his

business about the premises. When a new

porter, Hewlett, started who, like Allard, was a retired policeman, Cradock was

heard to mutter “place gets more like a

bloody police station every day.”

In an era of military conscription

it was customary for most boys to join the cadet force in their third year, as

it would advance their chance of officer status in the forces. I was not keen (albeit for probably all the

wrong reasons) on the idea of “playing soldiers” and rather taken aback when my

parents supported me. They felt that

there were already too many other activities which tempted me away from those

studies with which I was experiencing difficulty. I thus joined a few dozen other boys as

“Remnants”, usually spending the afternoon doing Art, or, in later years,

revising. I was regarded as a passable

artist, although at ‘O’ level Art was to be the only subject I failed. There were also craft sessions, involving

either woodwork or pottery. I never

succeeded in making any pottery ware, and at woodwork the nearest I came to

success was a shoddy plywood tray with beading round the edge which amazingly

survives as a firm base (happily hidden from view) for a standard lamp!

When I started at K.E.S. I travelled

by tram, a means of transport to which I was then devoted. But after a year the trams with their oak

and mahogany bodywork and brass fittings were replaced by ‘buses which I found

bland and lacking in character. I soon

transferred my interests to trains. On

half-days when there were no games a form-mate and I, clad in school caps and

full length navy blue belted raincoats, would drop in at Snow Hill station for

an hour or two on the way home to collect steam engine numbers. We usually waited until 4 o’clock when the Cambrian Coast Express came through on

its way from Aberystwyth to

The entrance from

gas-lit Edgbaston Park Road, showing the Governors’ Offices.

= = iii =

=

The outside world impinged on our lives at

school to only a modest extent. Perhaps

the greatest impact was that of the Hungarian Revolution in 1956 when boys were

encouraged to devise fund raising ideas to support refugees. General elections, won in 1951 by Winston

Churchill and in 1955 by Anthony Eden, provided brief excitement and boys with

access to the not-very-portable radios of the day found themselves in great

demand. The 1955 election coincided

with subsidence by the left-hand gate as one left school by the Main

Drive. This necessitated the temporary

closure of the gate and replacement of the sign urging one to keep left by one

requiring motorists to “Keep Right”: a

demand which seemed to coincide with the political allegiance of most

boys. The Suez crisis of 1956, however,

brought about more sophisticated political argument as heated exchanges raged

over the government’s intervention in Egypt.

As boys progressed up the school, so

they encountered different masters.

Older boys were taught Geography for ‘O’ and ‘A’ level by J.F. (“Uncle

Ben”) Benett, and by W.L. Whalley. The

former was fairly volatile, striding to and fro as he spoke. In the process, he often caught his gown on

his chair, with the result that the gown was slowly but surely being torn to

ribbons. Whalley appeared the gentler

character but was no soft touch. On one

occasion in my ‘O’ level course he was talking about grain production on the

Canadian prairies, supported by illustrations from a projector. He showed a picture of a tall grain elevator

alongside a river and asked the form what we could see across the river. Convinced of the genius of my wit, I shouted

out, accurately but unhelpfully, “A bridge”.

The rest of the form were kind enough to laugh moderately at my

contribution but Whalley was less impressed:

“Darlaston - out” was his terse response, and so I spent the rest of the

period contemplating the architecture of the corridor. Echoing the words of Sir Isaiah Berlin,

“Wal” would on such occasions describe teaching as “casting sham pearls before

real swine”.

My facetious answer was somewhat out

of character, as Geography was my best subject and so I was generally held in

reasonable favour by the masters. I

was, moreover, one of the team of weather observers who ran the school

meteorological station, supplying readings to the Meteorological Office, then

part of the Air Ministry. This entailed

someone attending the school every day, including Christmas Day. Entries had to be made in monthly returns

which stretched my modest mathematical abilities when it came to producing

figures for total rainfall and average maximum and minimum temperatures. I rose to the position of School

Meteorologist for my last two years, having the privilege of keeping the school

barograph during the holidays. This

gave me a fascination with these beautiful brass instruments which culminated

in the purchase of a barograph some forty years later, after my retirement.

Geography Room ’A’: This was the empire of Mr W.L.Whalley, but.

Parke seems to have taken over for the moment!

The barograph can be

discerned just below the folding projection screen.

The School Weather

Station: the thermometer screen (left)

and Cartwright demonstrates the rain gauge!

(These photographs were taken for the

display mounted on the occasion of the visit by H.M. The Queen in 1955)

Mathematics was proving the weakest

of my subjects and it was becoming evident that unless something dramatic was

done I would fail my ‘O’ level. Credit

for remedying this position must be given to Mr G. Cooper. A quiet man of infinite patience, he regularly

sat down at an empty desk by me and explained things repeatedly until I had

understood them. I was always to be

grateful for his work in getting me through ‘O’ level, although some boys had

their suspicions about him as he used hand-cream after handling chalk!

After my third year games ceased to

be compulsory. This was, to me, a

welcome change after the years of plodding round a Rugby field.

Cricket enjoyed a glorious reign in

my time at school – although, sadly, I made no contribution to that success. Contemporaries at school included O.S.

Wheatley, who was to become captain of Glamorganshire Cricket Club, and A.C.

Smith who became captain of Warwickshire and an England Test Match player. I liked cricket and, for once, understood

the rules of the game. My enthusiasm

was probably based largely on an aesthetic approach to the game, which

presumably accounts for my rapid loss of interest in professional cricket in

more recent times! With friends, I made

several visits to the County Ground at Edgbaston on school half days. One match to remember was the First Test

against the West Indies in 1957, where I witnessed the record partnership of

411 by May and Cowdrey. This was

followed by the spectacular collapse of the visitors (including Sobers) to 72

for 7 at the hands of Lock and Laker, before the match ended in a draw. But the simple fact is that I was no good at

cricket. I could neither catch the

ball, nor could I synchronise the bat in such a way as to hit the thing. My recollections now of school cricket are

of long spells fielding in the hot sunshine while sucking Spangles or Refreshers. On one occasion, by pure chance, I made

a catch to dismiss the opposing team’s last batsman, thus securing my house’s

victory. I was chaired off the pitch by

the rest of the team in traditional style, but the action was somewhat

ironical.

In some schools there is no doubt

that my general lack of interest in sport would have made me a marked man. But at K.E.S. there was a broad church of

pupils so that different attitudes and enthusiasms were happily accepted. The football cult that rules in other

quarters today was quite unknown.

Moreover, bullying, the bane of pupils at so many schools, was almost

totally non-existent and quieter boys or those with unusual interests were

happily accepted. Boys’ diverse

interests were well served by the wide range of societies which met after

school, often with interesting guest speakers.

Such societies included, inter

alia, Debating, Photography, Music, Railways, Drama and Archaeology,

although I did not participate in the activities of the last two and my

contribution to debates was minimal to say the least. In my last year I also joined the

Shakespeare Society which met to read plays on Saturday evenings in the relaxed

red leather comfort of the Cartland Room, where I like to think I contributed

near Gielgud qualities to such distinguished roles as Third Messenger and

Second Page.

Left: The Ratcliff Theatre, complete with blue

plush tip-up seats – and a fume cupboard at the left!

Right: The

In 1956 I took my ‘O’ levels, gaining

reasonable passes in Geography, Maths, Chemistry and Physics, and just scraping

through the rest of the subjects apart from Art. It was assumed that I would choose to do

Physics, Maths and Geography, a popular combination at ‘A’ level. But, I found Physics and Maths unrewarding. Literature and History seemed more

worthwhile and so I went into History Division to study History and English

along with Geography. Only one other

boy, Brown – known as D.G. to distinguish him from I.W. of that ilk-, had

chosen the same combination and the rest of the form did French instead of

Geography. This resulted in the two of

us having to do certain subjects in different groups from the main body of the

form. I was thus able unofficially to

drop the hated Gym altogether on the basis that one P.E. master thought I was

in the History and French set and the other thought I was in the Physics and

Maths set. At last I had escaped from

the torture of hanging like a trussed turkey from the wallbars, or, worse,

vainly trying to leap the vaulting horse.

The latter activity never seemed possible without a pain-inducing

collision, the suffering varying in intensity according to the portion of my

anatomy involved. To be fair, the usual

Gym instructor, “Sam” Cotter, was a genial man. More agile than his short, barrel-like

figure suggested, he usually stood still while issuing orders, military-style,

but occasionally surprised us by leaping into action. He reluctantly accepted the ineptitude of

the unathletic with a resigned tolerance.

I was taught English Literature for

‘A’ level by Mr A.J. “Tony” Trott and by K.G. Hall, a young master, christened

with the infinite wit of schoolboys as “Albert”. Tony Trott, who was Head of the English

Department, showed no false modesty and had an encyclopaedic knowledge of

literature. He responded to a challenge

by the form and identified correctly an obscure couplet from Henry VI Part

3. A natty dresser, with a taste for

exotic shirts and ties, he was very much the aesthete. His moment of glory in the 1950s was

undoubtedly his starring role in the Common Room performance of Peter Ustinov’s

Romanoff and Juliet. Trott played the indecisive president of an

impoverished central European state being wooed by Russia and the United States

whose scheming ambassadors were played respectively by Messrs Leeds and Hodges. Some years later Trott achieved more

permanent fame by writing an excellent and entertaining history of the

school. Nothing would stop Keith Hall

talking. He seemed to know everyone of

note in the world of literature (“As Lord David Cecil told me over

sherry…”). He would quote the opinions

of unknown American Professors of Anglo-Saxon literature, and never ceased to

remind us that he had studied Beowulf

in the original. (Didn’t all English

undergraduates at Oxford do so?) The

main problem was that he never seemed to mark or return essays we had handed

in. Although Hall was clearly highly

gifted, he was later to leave K.E.S. rather abruptly amidst a spate of

rumour. Another English master was

Peter Robbins, the England Rugby Football player. He had a disconcerting habit of doing his

exercises while lecturing, so that he would sit talking while raising and

lowering his legs, a heavy brief case being balanced on his feet.

I was now studying European History

with Charles Blount (who was to be my form master in History VI the following

year). Charles became a good friend in

later years. Studying with him gave a

real insight into the subject, with fascinating diversions into side issues. It was only appropriate that part of the

syllabus he covered included the Renaissance, for he was surely Renaissance

Man, knowledgeable on a host of topics both in the arts and science. Unlike many other masters, he was able

succinctly to explain a topic in a perfectly formed grammatical sentence, comprising

subject, verb and object, and without hesitation, repetition or deviation. This skill may have been aided by his

successful career as an author of history textbooks. With complex aspects of the subject he would

not trust our note-taking abilities but would dictate a prepared note. This would be divided up meticulously under

various levels of heading and sub-heading, starting with “Big Roman one”, and

working down through large and small letters to arabic numbers.

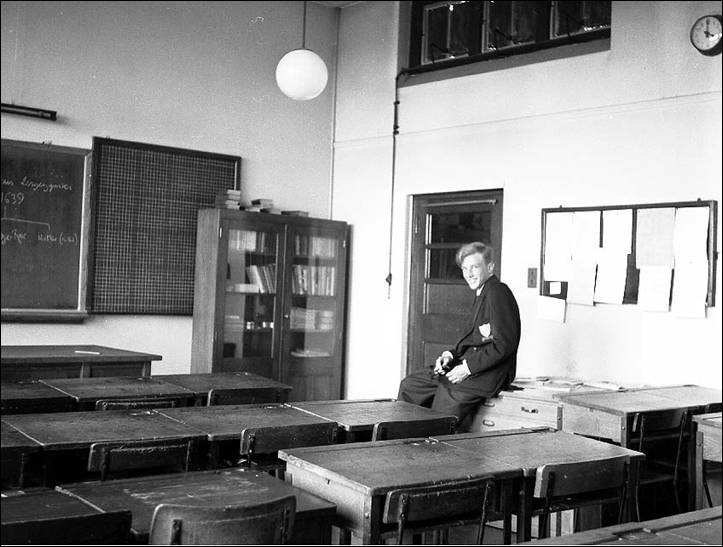

Room 174: Charles Blount’s History VI form room: Molyneux relaxes at 4 pm!

The

blackboard displays in Charles’s

handwriting the family tree of the Leszczynskis, a noble Polish family who

occupied a variety of government posts in the 17th century and

ultimately provided a king (Stanislaus)

and also a wife for Louis XV of

In most forms throughout the school it was necessary for boys to

“give a talk” on a chosen subject once in the year. In my year in Charles’s form I chose to talk

on the music of Elgar. When he knew of

my topic, Charles expressed great interest and provided invaluable technical

help in preparing musical examples.

Thus, I made the first of many enjoyable visits to his home, on that

occasion to copy old 78 r.p.m. records onto tape to provide illustrations for

the talk.

Several good friends were made in

the Sixth form, and the use of surnames in addressing them gave way out of

school to a more informal approach.

Such colleagues included Roger Guy (a geographer), and Jim Parke and Anthony

Mills amongst the historians. Bill

Oddie and David Munrow were also contemporaries, but I did not keep up the

friendship with them after school days.

Oddie was a prefect and always immaculately turned out – quite unlike

the image he was later to adopt on television.

In addition to his interest in natural history, he was a competent

artist, specializing in cartoon posters for school events, and he had an

enthusiastic interest in jazz. Although

Munrow was a keen and successful practitioner of music, he showed few

indications then of the tremendous success he would achieve in his tragically

short career as performer, composer and B.B.C. ‘personality’.

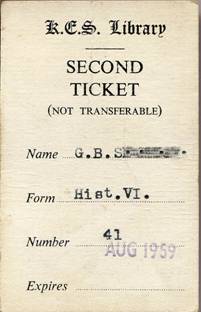

In my last two years at the school I

was School Librarian, which also involved working closely with Charles Blount. He had overall responsibility for the

library and my duties were to organise rotas of junior librarians and ensure

that the shelves and indices were kept in order and records of books lent and

returned were maintained. The routine

work thus involved was good experience for later years working in banking. Acting as School Librarian gave me very

valuable privileges. I had immediate

access to all new books, but, best of all, I shared a small but elegant office

with Charles Blount which became my ‘study’.

With carpet, damask curtains, desks and green leather armchairs, and

access to a vintage typewriter I had excellent facilities for personal study in

free periods. During my two years in

office there were a few other boys entitled to share access to the Librarian’s

Room, including Roberts, Dodwell, Walker and Coombes who later became Vicar of

Edgbaston. We turned the room into a

very homely base, even succeeding in making toast on the electric fire, although

on one bitter winter’s day it was necessary to open the windows to let out the

smoke from burnt toast before Charles came back!

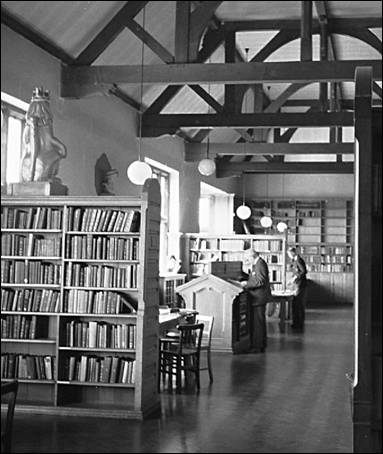

The

Library:

The Library: left: Mr J.D.

Copland stands at the Heath Memorial Library desk. Note also the ‘Queen’s Beast’, carved for the

1955 Royal Visit, and the bust of Edward VI.

right: Darlaston

at the card index while Molyneux, apparently in mafia guise, has him covered

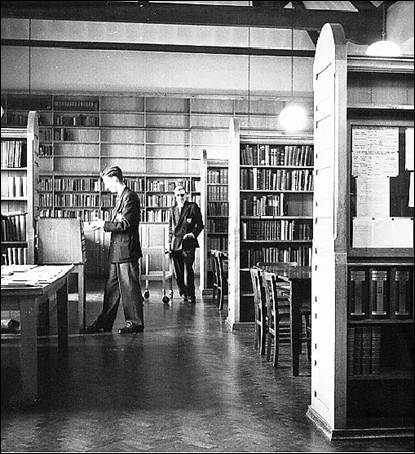

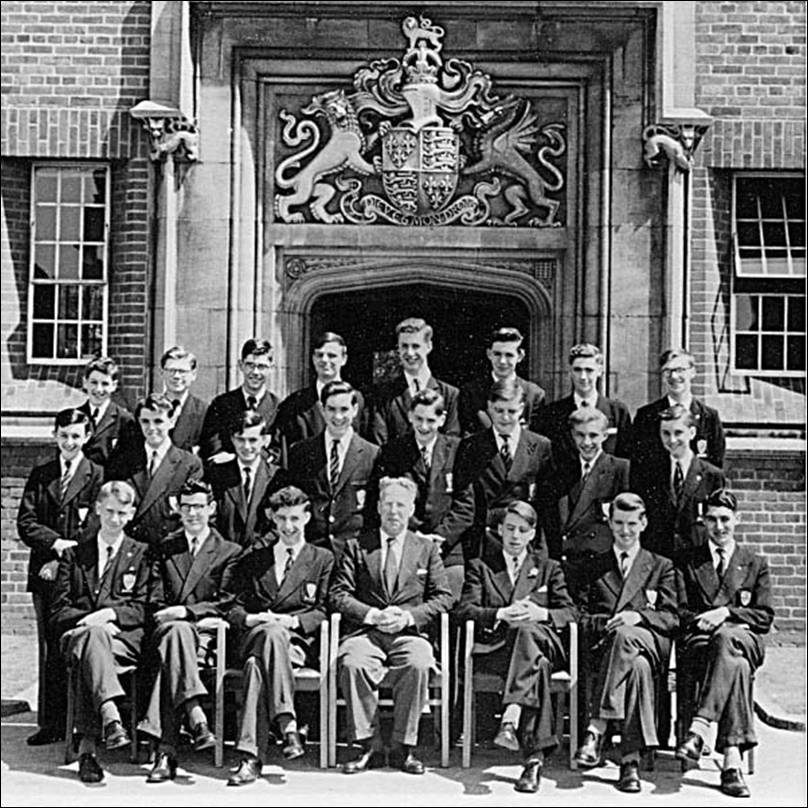

Librarians Line-up, 1958

(front row) Cartwright, Birch, Darlaston, Mr C.H.C. Blount,

Coombes, Walker, Bryant

(Photo by R.F.L.

Wilkins)

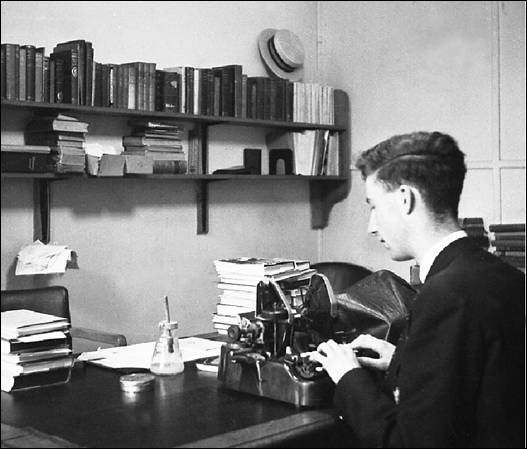

Darlaston in the Librarian’s Room,

attempting to tame the vintage typewriter

Note book suppliers’ bills on the

spike, Gloy for attaching book labels, and the inevitable boater

Saturday mornings in the Sixth Form

concluded with a lecture given by an outside speaker. Many well-known and entertaining people came

– and some who were, to me, neither well known nor the least bit

entertaining. The most enjoyable by far

was the percussionist James Blades who assured us that although he had provided

the sound effect for the gong which opened J. Arthur Rank films, the torso in

the film sequence belonged to a mere actor.

Less enjoyable was the gentleman from the Amateur Athletics Association whose

speech was like a Rolls Royce (almost inaudible and seemingly capable of

continuing for ever). He appeared set

to keep going for the afternoon, but was interrupted by Lunt in characteristic

manner: “I’m afraid I shall have ter

stop yer there, as parents will have soufflés waiting on the luncheon

table.”

Speakers on Sixth Form Speech Day at

the end of the summer term were more illustrious. Memorable visitors in the late 1950s

included Roy Jenkins, and Lord Denning who opened his speech by telling the

gathering that while he did not mind the audience looking at their watches when

he spoke, he would be hurt if they held them to their ears and shook them. After the formalities of Speech Day,

everyone adjourned to the playing fields for the annual cricket match between

the school and the old boys, with accompanying strawberry tea. This was essentially a social event where

mothers showed off their hats, fathers watched the cricket and boys tried not

to look too embarrassed by their parents.

The last day of the summer term

provided leavers with an opportunity for high spirits with no fear of reprisal

by authority. Most of the activities

were harmless fun, but a few involved minor vandalism or graffiti and thus

provoked official displeasure. Even

worse, it was not entirely unknown for young ladies from the girls’ school to

insinuate their way into proceedings.

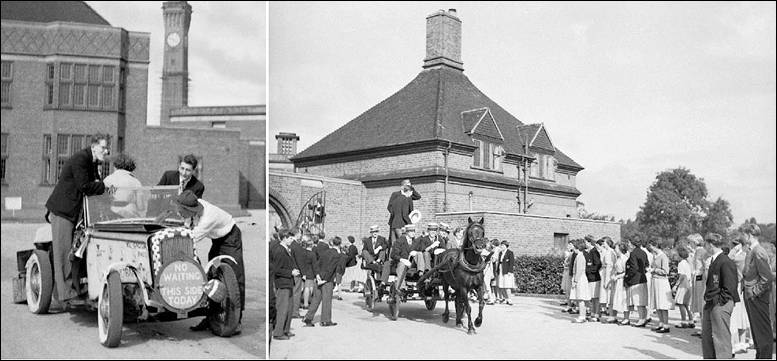

The most entertaining episodes involved senior boys arriving in a

variety of eccentric means of transport.

In 1957 these included a ‘tandem’ for three, a pony and trap, and a

short convoy of disreputable cars with an escort provided by the U.S.

Army. This episode offended Canon

Lunt’s sense of dignity as he was at pains to ensure that nothing disrupted the

sacred end of term routine. This

culminated in the singing of “God be with you till we meet again” and the

rousing School Song, beginning “Where the iron heart of England throbs beneath

its sombre robe/Stands a school whose sons have made her great and famous round

the globe/Great and famous round the globe…”

End of Term, Summer 1955: the girls of KEHS invade.

End of Term, Summer 1957

My ‘A’ level results in 1958 were, alas,

disappointing and inadequate for university entrance. I therefore stayed for an extra year for

another attempt, but it soon became clear that there would not be a place for

me at university. I stayed to complete

the year, retaking my ‘A’ levels, as by now a career in banking was looming and

better examination results would ensure a higher starting salary. But to a large extent the pressure on me

during my last year at school was lifted.

I had been at K.E.S. for almost eight years and the experience had changed

me from a child to someone equipped both to make a contribution to life in the

outside world, and to appreciate what the world had to offer. Moreover, associating with boys and masters

of outstanding ability had taught me a great deal about self-assurance. But above all, I had been privileged to

receive (in those days at no cost to the family) a first rate education in a

delightful environment with facilities and amenities of the highest standard.

With examination pressures largely

removed, my last term at school remains in memory as one of elegant ease,

enhanced by one of the finest summers of the century. I sauntered to school wearing a boater and

occasionally with a rose in the buttonhole of my double-breasted blazer. I was lord of the library and enjoyed my

privileged use of the Librarian’s Room.

If not unwinding in the comfort of its armchairs, I could relax in the

sunshine on the South Field or overlooking the swimming pool in the shade of

the Chapel. Occasionally, with friends,

one would take a relaxed afternoon stroll through the sunlit horse-chestnuts and

copper-beeches of Edgbaston, animatedly discussing music, or literature, or the

best trains to Much Wenlock. There were

still, of course, some lessons to attend.

One might have to dash off an essay on the domestic policy of Louis XIV

or the nobility of human nature evident in “King Lear”, but on the whole life

seemed to be a sweet succession of free periods and sunshine. Cold reality would catch up with me before

long, but that enchanted summer of 1959 remains a grateful memory of another

world.

=========================================================================================

The South Front with

‘Old Joe’, the University Clock Tower modelled on the Torre di Mangia at Sienna

prominent at the left.

The Gyms are to the

extreme right

A detail from the

official 1959 School photograph with a selection of masters:

Messrs: J. Hodges,

T.G. Freeman, A.J. Trott, W.L. Whalley, J.B. Hurn, W. Traynor, W. Buttle,

L.K.J. Cooke, J.B. Guy, F.L. Kay.

Another detail from

the 1959 School photograph with a further selection of masters:

Canon R.G. Lunt,

Messrs: H.W. Ballance, J.C. Roberts, A.E. Leeds, W. Barlow, N.J.F. Craig,

the Rev F.J.

Williams, C.H.C. Blount, G.C. Sacret.

==========================================================================================================

A reminder of the

glorious summer of 1959:

School v Old Edwardians, Eastern

Road, Speech Day July 1959

==========================================================================================

and, finally, a few holy

relics which have survived the passage of the last forty-fifty years:

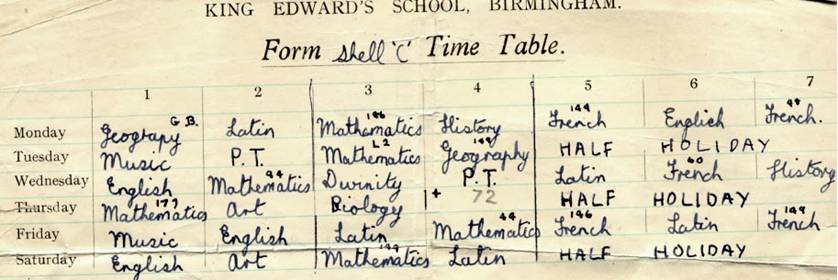

Shell ‘C’ timetable: September 1951

(The small figures indicate

room numbers!)

At that time C.C.F. activities

were held on Thursdays, commencing after break.

Friday was a normal full day.

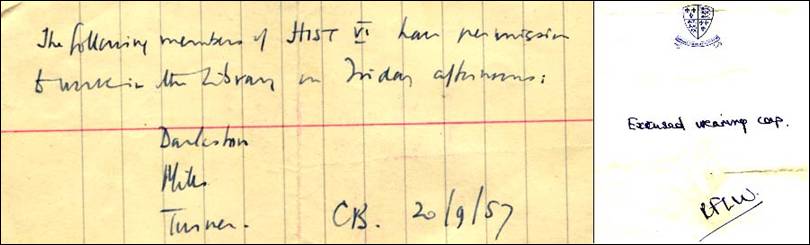

A ‘chit’ from Mr C.H.C. Blount

and a “cap pass” issued by R.F.L. Wilkins, a prefect.

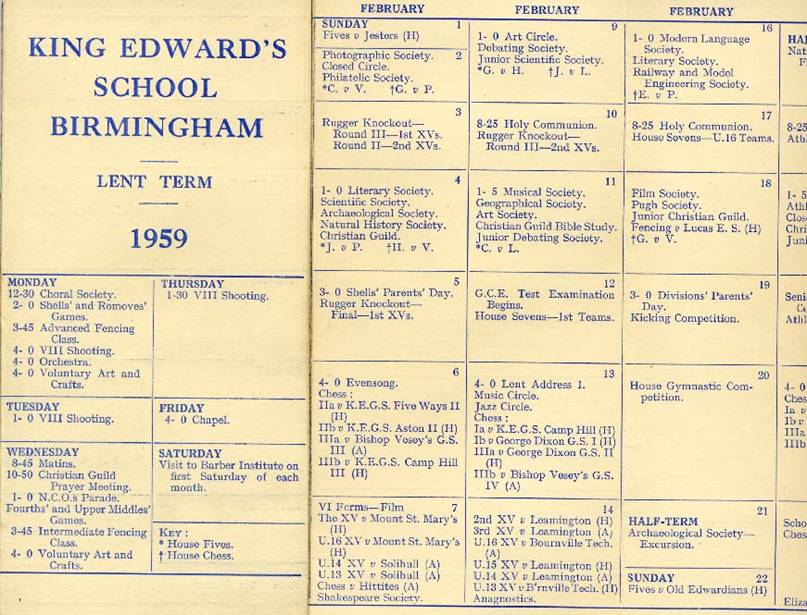

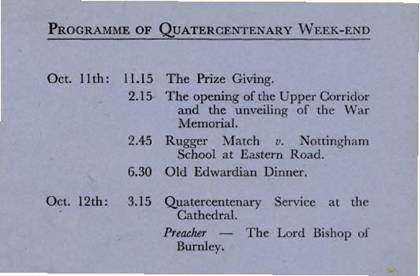

School Calendar

Quatercentenary programme

(1952) and a Library Ticket

A “Dinner Ticket”

A 10d (=4p) passport to

Miss Chaffer’s culinary

glories.

You

might also be interested in the following further pages, both with many

photographs:

MemoryLane2.htm

(Robert’s childhood memories of the war, early days at school, food

rationing, a spell in hospital, and other boyish memories!)

FamilyTrees.htm (Family history, including tentative links back to 1373, in

the reign of King Edward III !)

A

few contemporaries revisited the school in 2006: here are our impressions on returning to the

scene of our past endeavours:

HALF A

CENTURY ON

A grey

winter’s day saw three contemporaries from the intake of 1951, Roger Bickerton,

Patrick Walker and the writer, together with wives, take up Derek Benson’s

offer in the Gazette of a conducted

tour of the school. It proved a

fascinating day which we recommend to any other Old Edwardians who have not had

a chance to revisit the scenes of their youth.

In the 45

years since we last trod those corridors there have been some remarkable

changes! Passing through the Main Door,

we found the dreary cloakrooms and locker rooms have long gone. Instead of the Porters’ Lodge, forbiddingly

occupied by Allard or Cradock, we were welcomed by a lady receptionist

presiding over an area with comfortable chairs, magazines and attractive

engraved glass screens. We were quickly

taken for coffee, served in a Common Room which bears no resemblance to the

crowded smoke-filled room briefly glimpsed in the 1950s. It has grown to absorb much of the

Moving to the

South Front, we found the cloisters with the Tuck Shop and Changing Rooms had

given way to a splendid array of new form rooms for the Classics Department

which we would shortly inspect. There

was also a small anonymous looking door, which Derek said led to the Tuck Shop,

but whose appearance seemed to owe more to a

On returning to the School, we entered territory new to us all: the new Classical Corridor. Despite its relatively recent construction, we agreed that it had the authentic ambience we recalled from our schooldays. It was particularly good to discover that the Classics Department apparently thrives in an era when Latin and Greek have vanished from so many schools’ curricula. Next, we dropped in on Room 48 which was obligingly empty. Here, despite changes, was the true form room atmosphere we remembered so well! The passing years have seen the advent of the computer, the covering of polished floor blocks by carpet, replacement of black and yellow chalk boards by white boards and marker pens, and removal of the masters’ dais so that staff are brought down to the same democratic level as their pupils. But this was still recognisable as holy ground where in the 1950s “Sacco” had attempted to give us an understanding of subjunctives and pluperfects. If anyone thought I displayed a nervous twitch, it was because I was half expecting that once familiar voice to call out “Darlaston, I am still waiting for you to hand in your prep. Fifty years should be long enough even for your modest abilities.”

Next door, the Geography Department was much changed from the days of “Wal” and “Ben”. The balconies, almost never used in the 1950s, have been enclosed and doors realigned to provide useful additional administrative space. Here I noticed an old friend, the barograph, which in the Sixth Form accompanied me home in the holidays so that full records were maintained. But it had stopped, and of the old weather station which provided statistics to the Meteorological Office in the 1940s and 1950s, nothing was to be seen: a sad loss of an interesting and rewarding topic.

It was time for lunch in the Dining Hall, a building which seemed little altered from the past, although the squeaky trolleys with stacked meals distributed by boys have given way to the inevitable self-service system. The quality of the food has, however, changed beyond belief and we all enjoyed an excellent meal.

Big School,

still dominated by Sapientia,

remained as impressive as we all remembered it;

although because of fire safety regulations there is now an additional

access to the Organ loft. Such

requirements also restrict the numbers permitted in

We next had an appointment with the Chief Master, Roger Dancy, and we were especially grateful to him for giving us his time on a busy day. Our discussion with him was more genial and relaxed than those on some earlier visits to the Chief Master’s study!

The Cartland

Club no longer exists and its room is now used for English: possibly, as Derek said, the smartest form

room north of

The Language Department had changed beyond recognition in this age of computers. We were shown the latest in touch-screen technology, but sadly it was not working because, we were told, a squirrel had gnawed through the cable: the KES equivalent of leaves on the line, I suppose. Progressing along the upper corridor, we were alarmed to see that the entrance to Charles Blount’s old room (Room 174) had been bricked up and plastered over. Momentary fears that Charles and History VI had been immured, frozen in time at Big Roman One, were allayed on discovering a new entrance direct from the Library which has appropriated Room 174 for its own use. The Library itself remains a most impressive feature of the school; although here too the polished blocks had been covered by carpet. The elegant Heath Memorial reference desk has sadly been removed, but replaced by a well-equipped information centre. We enjoyed a pleasant discussion with the lady Librarian: a full time post which has given the Library a more active role in assisting boys’ studies than in the past.

Inevitably, since the 1950s there have been far-reaching changes in the Science Department. New rooms and laboratories seem to fill every space and this is clearly a thriving and well-equipped part of the school. The casual demeanour of former years – boys conducting experiments in shirt-sleeves – has given way to an era of protective clothing, including goggles. In our day, the science block ended at Lecture Room 3, later the Ratcliff Theatre, equipped with tiered plush seating and a curtained cinema screen with a projection room at the rear, where cinema films were once shown in fine style. This has been swept away, making more room for laboratory space, but it does seem a regrettable loss.

The modern Design Centre is equipped with an amazing array of equipment for art and for work with wood, metal and plastics. The exterior of the block is quite attractive, if not wholly in keeping with Hobbis’s design, but the interior is most unusual, giving the appearance of having been designed so that every journey, no matter how short, involves a few steps up, a short metal landing, and more steps down again! But there is no doubt that the boys here learn useful skills not available to their predecessors.

Time was running out, even though there were parts of the school, including the Music Department and Eastern Road, not visited; and so, not for the first time, we found ourselves heading up the Main Drive at 3.45 in the afternoon. But even here there was a variation from old practice: girls, leaving KEHS, now take a short cut from their building so as to join the boys’ drive, making their exit past the Foundation Office. That was not something to have been tolerated by Canon Lunt who famously telephoned the girls’ school Head Mistress to complain that one of her ‘gels’ was in his drive and would she kindly have the trespasser removed!

We had been treated like royalty (indeed, we had seen a great deal more than was vouchsafed to Her Majesty on that wet day in November 1955) and had witnessed a great school hard at work. Despite the occasional flamboyant young gentleman with shirt worn outside the trousers and some pretty sloppy ties, the boys are an impressive bunch who looked keen to go about their studies. We spoke to several members of staff who were clearly committed to their work and who were excellent communicators.

Numbers at the school have grown since the 1950s, so that the buildings seem rather more crowded and frenetic. Then the school was almost entirely populated by middle class, white males. Today such distinctions no longer obtain. The number of boys of Asian origin is testimony to the fact that their parents show greater enthusiasm for paying fees for education than do those of the indigenous population. The male domination of the staff is still maintained – but eroded by the steady growth in the number of female teachers (dare one refer to them as Mistresses?) This, coupled with the need of a fee-paying school to appeal to parents “of taste and discernment” has led to a gentle feminisation of the school. The good old boys’ school tradition of calling people by surnames has yielded to the general use of Christian names. Roses bloom by the Main Door and potted palms adorn the South Door. Attractive décor is essential.

Yes, we were all impressed. For the males in our group there had been the opportunity to indulge in unalloyed nostalgia while enjoying a glimpse of the wonderful opportunities available to the rising generation. For our wives, there was the chance to discover something about the place which made their husbands what they are, and which still comes into conversation on so many occasions. We all left hoping that the School continues to go from strength to strength and resolved to do our bit to help that cause by making our own contributions to the Bursary Appeal.

Robert Darlaston

If other

pages are not listed to the left, the Home Page can be accessed here: www.robertdarlaston.co.uk