This Web Page is Memory

Lane (First set up 2006;

latest minor alterations, 1st April 2018)

Please note: there are more than 30 photos:

these may take a while to download!

Harebells on the Common

A Birmingham

Childhood Remembered

These pages include some memories

of my childhood, dug out of the deepest recesses of my mind, concentrating

where possible on episodes which illustrate how life in the 1940s differed from

that we know today. I have tried to

choose incidents which might amuse, but including topics both serious and

saucy: all part of the process of

growing up in the post-war era! I hope

this account entertains others and ring bells in their own memories. The 1940s were a grey world of coal smoke

and gas-lit streets, of Winston Churchill and Clement Attlee, Spam* and

steam trains, mangles and woolly vests.

There were no mobile phones or DVDs, no televisions or refrigerators, no

foreign holidays or central heating, no computers and very few motor cars. But it was the only world I knew as a child

and I was well content with it.

(* Spam was tinned meat and had nothing to do with computers!!)

CHILDHOOD AND SCHOOLDAYS

1943 – 1951

Robert Darlaston

Childhood is measured out

by sounds and smells

And sights, before the dark of reason grows

John Betjeman

Summoned by Bells

Index to Contents

Early Years My first hazy

memories – 1943

Wartime

Birmingham Air raids; trams and buttered toast; shopping and the cinema

South Wales Holidays Farms, seaside and “The Resurrection”

Domestic

Life in the 1940s Clothes, wash day, Christmas

and starting School

Worries

about Health Tonsils and small boy stuff. Discovery of a chick

A Hard

Winter Snow and fog, 1940s

style

School Days Lessons and play at

Amberley Prep School; a glimpse of stocking tops

Children’s Hour Wireless, and Ladies to

tea: I meet the constabulary

A Balanced

Diet Meals, rationing and days

out

The King

Passes by Glimpses of the King and of

Russian leaders

Changing

Times I am impressed by the news

and also by Silvana Mangano

A New School Moving to King Edward’s,

The End of an

Era A Festival, a Funeral and a

Coronation

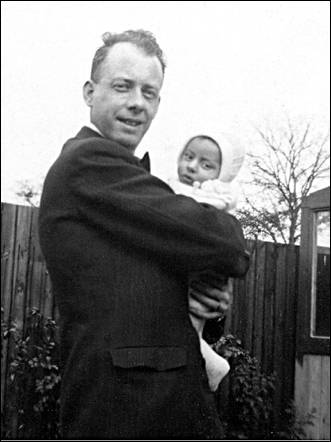

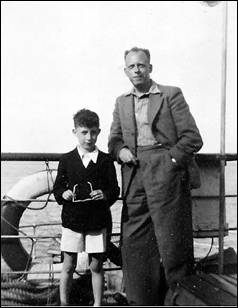

With my

parents in 1940 and 1942 in the back garden

|

T |

he occasion when I first noticed my mother wearing trousers was,

for me, so sensational that it remains imprinted on my brain as almost

certainly my earliest memory. It was a

cold night in April 1943. I was not yet

three years of age. The air-raid siren

had just gone and my parents and I were in the dining room, the windows

securely covered by the thick blackout curtains made by my mother, who, in an

effort to relieve wartime austerity, had trimmed the hems with decorative tapes

of green and gold. For no particular

reason, I was sitting on the cross-bar beneath the dining table. We were about to go into the cold night to

settle down once again in the air raid shelter. It is a memory inextricably tied up with the

below-ground smell of damp earth and of the methylated

spirit lamp that illuminated our tiny shelter, built into the garden

rockery. The event can be dated

accurately, because it was the first air raid for several months and thereafter

raids ceased to be a regular occurrence in the Midlands. There are other associated memories: waiting before an air raid, the tension

tangible in the anxious atmosphere:

being told not to suck my thumb after playing on the floor “because of

the danger of picking up germs” – or was it Germans? The words were puzzlingly similar to a

two-year-old.

We cling to our early memories as the starting point of our

life’s journey. For me the underlying

theme from those days was war: war

against a society so evil it is now hard to realise that it existed in

I was an only child, born on 23rd June 1940 at 1.35

p.m. at

Castle

Bromwich Church, where I was Baptised

Looking

towards Castle Bromwich from Hodgehill Common

Like most children, I

have many random early memories: a ride

in the pram, a harsh word here, a tumble there; of the fun when my father surprised me

by hiding in the pantry, and of the panic when I wandered off to explore alone

while my mother’s attention was distracted in the local butcher’s shop. But unlike the air raid memories, those

cannot be dated. Then there are those

wonderful impressions left in the childhood mind by patterns; shadows on a carpet; enchanting designs on curtains or wallpaper. Wallpaper played a significant

part in my life at an early age. After

lunch each day I was put in my cot for a sleep, but there was a time when sleep

would not come. I lay awake and was

bored. Through the bars of my cot I

could see a small irregularity in the wallpaper. I recall teasing at it with my

fingernail. Oh joy! I could peel a

little bit off. A bit more effort and

off came another inch. This was the

most satisfying thing I had ever done.

I set to work with gusto and can still remember the sensuous pleasure of

peeling off strips of paper.

Eventually, my mother arrived to check on her sleeping infant, only to

find a joyous child surrounded by shreds of paper. Suffice it to say that I was never put down

for another afternoon nap.

Paper of a different sort provided further entertainment when my

mother, unable in wartime to obtain the usual brand of toilet roll, bought

instead a box of interleaved lavatory paper (always hard and shiny in those

days). I was fascinated by the apparently

endless supply – pull out a sheet, and, hey presto! – there

was another. Anxious to get to the

bottom of this (sorry!), I kept on pulling sheets until the lavatory floor was

invisible beneath paper and the box was empty.

Once more, I was surprised to find that my mother did not share my

interest in research into paper production.

It is to my parents’ credit that the nocturnal trips to

the air raid shelter caused me no major worries, other than frustration at my

father’s refusal to let me have a battery in my torch. I suppose he had an understandable

reluctance to let me wave it in friendly greeting to the Luftwaffe flying

overhead. The war was, despite my own

lack of concern, the inevitable background to life and everyone told me how

everything would be “different when the war ended.” News was so dominated by the war that I

believed that when peace came “news” would cease. I now look back, amazed at my good fortune

in being so well insulated from the horrors of those years, and I find myself

more than ever unable to comprehend how, in my own lifetime, men in Europe, a

supposedly civilised continent, could inflict such unimaginable suffering on

one another. My only memories of the

end of the war are of a street party in

Wartime

Picnic

This photo is proof that there were happy, light-hearted moments

during the war.

My parent and I (we are at the right of the group) are enjoying

a picnic with the Godsall family who lived

a few doors away. Their daughter Jill became a pianist and

remains a good friend. The photo was

taken in 1942, but the location is, alas,

forgotten.

1943: Ready to go shopping : my 3rd birthday: on the

big red engine

There were always Lupins in the garden on my birthday

Some

manifestations of war did cause me alarm.

There were sinister gaps in nearby rows of houses where willow herb grew

among the rubble. Sometimes an interior

wall was left standing, exposed to the elements, leaving the last residents’

taste in wallpaper for all to see.

There was also the vast ruin of the sauce factory to be seen from the

tram going into Birmingham. One bomb

landed less than 100 yards from home, sucking open the French windows: I was too young to recall the incident, but

the damage to the window frames remained evident until they were replaced

twenty years later. There were baleful

barrage balloons moored on Hodgehill Common and, from

time to time throughout the war, convoys of tanks would pass our house, driven

under their own power, the steel tracks making a deafening racket on the road

surface and sending me scuttling indoors in search of quiet. Worst of all were low flying aircraft, which

terrified me by day and haunted my dreams at night. In 1940, while only a few

months old, I had been in my pram in the garden when a plane came over, flying

very low. My mother rushed

outside and looked up in time to see a plane with the German cross and (she

said) a Nazi pilot peering through the cockpit window. She grabbed me in terror and fled to hide

beneath the stairs. (The pilot,

probably equally terrified, was apparently soon brought down some miles

away). Of course I can have no

recollection of that incident, but did my mother’s terror somehow impress

itself into my slowly developing mind?

Even today, the sound of a jumbo jet climbing overhead can provoke an

involuntary shiver.

But there are pleasant memories too; of lazy summer

afternoons when I picked harebells for my mother on the nearby grassy common, and

of shopping trips to town. In “Summoned by Bells” John Betjeman

recalled his childhood as “safe in a world of trains and buttered toast”: in my world trams and buttered toast were the features which linger in the

memory. We went shopping by tram and my

mother always concluded the afternoon with a call at “Pets’ Corner” in Lewis’s

department store, to see the monkeys and parrots, followed by hot buttered

toast at the Kardomah café. After I started school the trams in their

attractive dark blue and primrose colours became a vital part of my daily

life.

Transport of Delight:

left:

a

right:

the lower deck of the same tram, showing reversible seats.

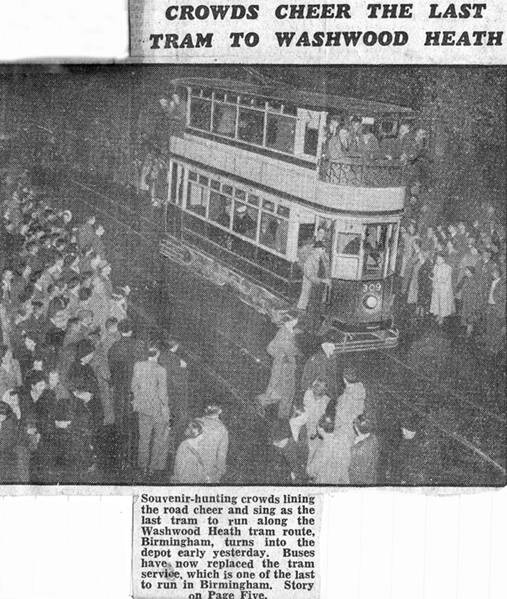

October 1950: How the last tram on the No. 10 route was

seen by the long-defunct Birmingham Gazette.

I had travelled this route daily on

my way to and from school and sorely missed the trams with their fascinating

character: a souvenir ticket (“Ha’penny child’s”) reminds one how

inexpensive tram travel was in the 1940s.

A special treat in the summer holidays would be the tram

ride to the Lickey Hills on the Worcestershire

border: a twelve-mile journey across the

city, taking over an hour. Tram seats

had reversible backs so that one normally sat facing the direction of travel,

but one could leave a seat unreversed enabling a

party of four to face one another as a group, just as on a train. At the city centre terminus passengers left

the tram at the front while new passengers boarded at the rear. This gave small boys the irresistible

temptation of treading on the driver’s pedal which mechanically sounded the

gong – the tram’s warning equivalent of a motor horn. For the latter part of the journey from the

city to the Lickey Hills the trams forsook the

streets for their own right of way, bowling merrily along through the sunlit

trees at 40 m.p.h.

We would lean happily out of the window, taking care to retreat as other

trams passed close by in the opposite direction. Once at the Lickey

terminus everyone would want to rush off to the hills, but I would try to

linger and watch the conductor placing the trolley pole on the overhead wire

for the return journey;

no easy task if the sun was in his eyes.

Shopping trips to the centre of

Holidays in

Wartime holidays had been confined to annual trips to my grandparents

who farmed in

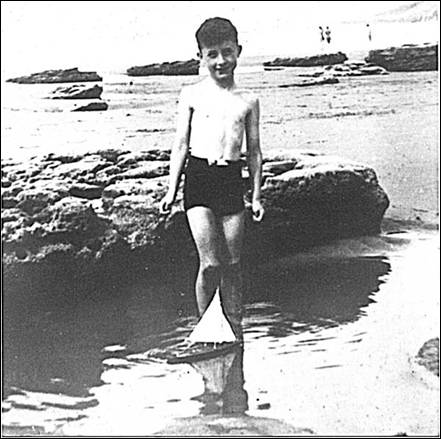

Paddling in a

rock pool at Southerndown, 1949; and by the Morris 8 motor car after

changing for the beach, in 1950 (note the old AA badge on the car’s radiator

grill).

As a small child I was bored by the

journey to

On

the way to South Wales: floods near

the

progress of a gypsies’ vardoe on 3rd

October 1958

At Gilfach my grandparents did not

occupy the traditional farm house, which was deemed too primitive, but lived in

a double fronted Victorian villa (“Oak Cottage”) 200 yards away. This was scarcely any more luxurious. Electricity was confined to the downstairs

rooms, so I went up to bed by candlelight (logic decreed that as one only slept

upstairs, there was clearly no need for electric lights there!), and I settled

down to sleep with an embroidered text above the bed saying “Simply to Thy

Cross I cling”. There was no hot water

and no cooker: my grandmother used the

coal fire with a traditional oven alongside, producing wonderful meals. In the bedrooms there were chamber pots

beneath the beds, and marble washstands with china jugs and basins which would

now be collectors’ pieces. Of the

primitive outside lavatory arrangements at Oak Cottage, the less said the

better. But some farmhouse facilities

were even more exotic, with a long walk to the privy in the orchard where one

might find a commodious building offering accommodation for two patrons seated

on a timber bench side-by-side, and (in one memorable location) even a three-seater for that special social occasion!

Staying at Gilfach

introduced me to farming routines almost unchanged over the centuries. I would accompany my grandmother to collect

eggs warm from the chickens who roamed free on the bracken-covered

hillside. I would watch my grandfather

with other local farmers as they dipped or marked the sheep. I would play with his sheepdogs, who, when

they thought duty called, would abandon me and rush off to attend to the sheep

which they found more absorbing than a small boy. On a fine summer’s evening Grandad would put me on Ginger, his old mountain pony, for

a ride up to the paddock: I felt like a

maharajah.

But one Welsh journey in 1945 was more alarming. We set off to a remote Welsh valley to find

the farm which was to be the home of Auntie Maud and Uncle Len, then

newly-married. Signposts were still

almost non-existent following the war.

Cloud and fog clung to the mountainside and the drenching rain drifted

across in soaking sheets. As the

Morris climbed slowly into the all-engulfing mist, with a sheer drop of 200

feet at the side of the road, we passed whitewashed signs on the bare rock

face: “Prepare to meet thy God”. Was this to be our final journey? But when we reached Gelli Farm I found a

place which was to me, as a city child, close to heaven in more childlike ways: 3000 acres of freedom.

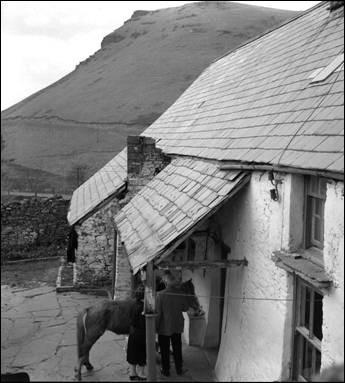

Gelli farm scenes in the 1950s:

Cousin Eiryl’s

pony waits for her outside the farm house.

A cow approaches, ready for milking as young riders look on.

In wet weather such farmyards would be a

sea of mud and wellington boots the only possible footwear.

At the Gelli I could escape into a carefree world of the

imagination with mountains to climb and streams to dam – in the imagination,

Everest and the Nile lay before me: who

cared if my shoes and socks were soaked through, or if the forgotten chicken’s

egg, placed carefully in my trouser pocket, smashed when I went sprawling in

the tussocky grass?

But in those drab, chill post-war years, the unimaginative adults were

more concerned about the lack of electricity, the enormous fireplace with its

chimney open to the sky, and with the ivy growing indoors on the damp, peeling,

farmhouse walls.

Throughout

the later 1940s and all through the 1950s my grandfather would stay at the

Gelli for a few days from time to time to help out at shearing or other busy

times. Horse and dogs would be

essential once he arrived there and began helping with gathering the sheep. His generation never took to motor

transport, so when it was time to start he would mount Ginger, call his dogs

and they would all set off from Gilfach across the

bleak mountain tops for the twelve mile journey, following the old drovers’

tracks which had been the traditional routes for farmers for many

centuries. To my grandfather this was

more natural than following the motor road round the valleys which was half as

long again and, even then, busy with motor traffic. But farming methods were soon to change,

even in the Welsh mountains, so Grandad was perhaps

the last man regularly to use the old drovers’ roads of South Wales.

Grandad about to

set off from Gilfach on Ginger

Other favoured destinations when we stayed in South Wales

included Barry with its wonderfully tawdry funfair and its miles of docks, then

alive with shipping, and Mumbles with its electric railway around the bay from

Swansea. Nor must one forget those

day-long steamer trips when the Glen Usk, the Britannia,

and the splendid new Cardiff Queen

would take us to

Visits to

In

those childhood days central heating was almost unknown and only one room in a

house would normally be heated, by a coal fire, although the kitchen might also

be warm from cooking. Thus, for much of

the year one expected to be cold as soon as one moved away from the fire and

going to bed on a winter’s night was an especial ordeal. So instead of wandering about the house (as

is now customary) in shirtsleeves, I would as a child wear thick woollen

underclothes (knitted by my mother – how did I tolerate wool next to the

skin?), a grey shirt of a substantial Viyella-type

material, a long-sleeved woollen pull-over (also knitted by my mother) and a

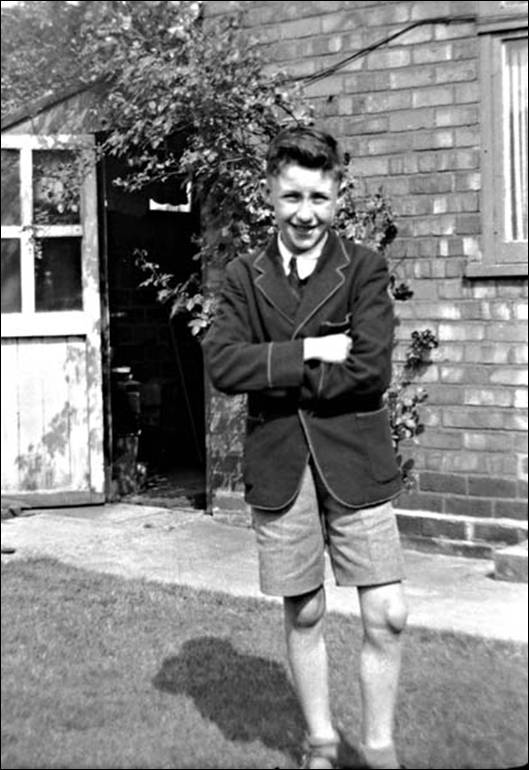

heavy school blazer. There were usually

two blazers on call: one was new and too

large and was worn to school, the other was old and too small and was worn

about the house and for play. School

caps, scarves and gabardine raincoats were added for out-door excursions in all

but the warmest weather (and sometimes even to the beach if there was a chill

wind). By contrast, short trousers were

de rigeur

up to 13 years of age. In consequence, knees, habitually exposed to the elements and to frequent

close encounters with the ground, were frequently chapped and scarred.

With a fire in only one room, winter

Mondays were especially miserable to a child, because Monday was washday and if

the weather was wet the washing would be hung to dry on a clothes-horse in

front of the fire. I recall Monday, 23rd

December 1946 as the longest and dreariest day of my life. Outside it was cold and damp. There was steaming washing arrayed in front

of the fire, the windows were running with condensation and my mother was busy,

pre-occupied with ironing and mince-pie manufacture. The rest of the house was chilly and

unwelcoming. I was bored and

bad-tempered. I wanted Christmas to

come quickly, but time seemed to be at a standstill. Eventually, after what seemed more like two

weeks than two days, Christmas arrived and brought a rarity: a red clockwork

engine, number 6161: no rails, for the

war was but recently over and toy production was limited. Soon after breakfast tragedy struck, for the

engine, on a fully wound spring, shot across the floor like the proverbial bat

from Hades, and wedged itself underneath the sofa, crushing its tinplate cab in

the process. There were tears, but my

father was on hand to administer repairs, and the engine returned to service in

fair, if not pristine, condition.

Presents at Christmas arrived

mysteriously, during the night, in a pillow case at the foot of my bed until I

was thirteen years of age, by which time the identity of Father Christmas had

long since been established. One

wartime Christmas, my main present had been a Golliwog, carefully made by my

dear mother, arranged with his head peeping out of the pillowcase. No political correctness in the 1940s!

165 Stechford

Road: the frontage and the new pond in

1949

I had started school in May 1945, shortly before my fifth

birthday. My parents chose to send me to

Amberley Preparatory School, a small private school on Coleshill

Road about a quarter of a mile from home, although it was later to move a mile

further away to Ward End. I seemed to

get on well, but after a few months had some sort of minor breakdown (which I

do not remember, and which was never discussed, although I do recall hearing

myself described as “highly-strung”!)

Thus, for about a year I only went to school in the mornings. I had been attending school for scarcely a

year when I was required to take part in an event which would not have been out

of place in Dickens. The school was a

small affair in a Victorian house, run by two unmarried ladies, Miss Major and

Miss Ainsworth. Sadly, quite soon after

my arrival, Miss Major was diagnosed as suffering from a terminal illness. At her request, as a farewell gesture, the

entire school (about fifty children) had to process slowly through her bedroom

on the top floor. As children we

accepted this strange ritual as just another everyday

event, but my mind now gives it the quality of an event in a Dickens novel or,

maybe, a sentimental Victorian oil painting, vast and dark, perhaps by Arthur

Hughes or R.B. Martineau: “Miss Major’s

farewell to her young pupils.”

Many random memories were acquired over those early

childhood years, often involving smells:

lilac blossom and wellington boots, privet hedges and coke boilers. But when I was five I experienced a

recurrent bad throat with associated nasal problems. So, in accordance with the contemporary

medical practice of removing all such evidently unnecessary items of anatomy, I

went into the Birmingham Ear, Nose and Throat Hospital to have my tonsils and

adenoids taken out. This was a major

upheaval for one who had so far led a very sheltered existence. It thus became the first event in my life to

imprint itself on my mind complete in almost every minor detail, from beginning

to end.

For a start, it was unprecedented in those days of petrol

rationing to go into the centre of

But I soon had my revenge. For the first (and, I believe, only) time in

my life, I got a girl into trouble. On

emerging from the anaesthetic I had a raging sore throat. I uttered those famous childhood words: “I want a drink of water.” The ward was under the control of a Sister

who appeared to be related to Wagner’s Valkyries. She told me firmly that I could not have a

drink. A few minutes later a pretty

young nurse passed by. (Even at five

years of age, I could appreciate a pretty girl). I repeated my request and she kindly

produced a drink. Ten minutes later the

Valkyrie flew past and noticed the empty cup (of a

celluloid-type material – ugh!). “WHO

gave you that drink?” she demanded. I

remember my reply. Precisely. Word by incriminating word: “the NICE nurse gave it to me.” The sharp intake of breath seemed in danger

of making the walls implode. The Valkyrie mounted her invisible steed and stormed off on a

punishment mission. For the first, but

not the last time in my life, I knew I had said the wrong thing.

In the years following the hospital visit, health matters gave

me several worried moments. I suffered

the usual childhood ailments in turn – Whooping Cough and Chicken Pox one year,

Measles and Mumps the next. But my most

serious health problem in childhood occurred at about seven years of age, when

I developed Ulcerative Colitis, which was dubiously blamed on the bland wartime

diet. It meant that for several years I

was not allowed to eat any fruit unless all the skin and pips had been

removed. A far more serious worry in

the 1940s was tuberculosis, then widespread and often fatal. Our neighbour’s daughter and the brother of

a school friend had both contracted the disease in their late teens and had

been in sanatoriums for many months.

Happily, they both recovered, but the fear of being carted away from my

home in such circumstances did not bear thinking about. Then there was an absurd worry, typical of

the fears teasing a small boy’s mind in a sheltered and solitary

childhood. This began when I noticed a

minor personal difference from the other boys who contributed to the hospital’s

communal chamber pot. Despite being a

subject of immense fascination to growing lads, it was not the kind of thing

discussed in the best circles in the 1940s.

Thus, fixed in my mind as a strange and worrying abnormality, it caused

me much anxiety for several years until communal school showers revealed that

the difference schoolboys knew as “Cavaliers and Roundheads” was, after all,

not uncommon. It was to be over fifty

years before I learned that in those pre-N.H.S. days the required surgery had

been performed not in hospital, but one afternoon on our kitchen table by Dr

Lillie. There was no anaesthetic for

the infant patient, but the genial Scots doctor had (as my mother tartly observed)

first fortified himself with rather more whisky than seemed advisable for one

about to wield a surgical knife! Such

operations were then doubtless a welcome supplementary source of income for a

G.P. I might add here that in

accordance with the prim standards of modesty of the day, I was even longer to

remain ignorant of the far more interesting structural differences between

males and females. My parents had a

small female nude statue on the mantelpiece, but I attributed its lack of

masculinity to good taste and decency on the part of the manufacturer. Once, when I was about eight, a girl who was

a playmate persuaded me to strip off for her edification, but, alas, reciprocal

facilities were not on offer, so in an era when nudity was never seen in public

my innocence long remained intact!

But in 1946 there was another event

of much greater amusement to a five-year-old than health or bodily

matters. The week before I went into

hospital my mother and I had found a day old chick. It was squatting, fluffed up against the

cold March wind, on the pavement of an otherwise deserted suburban

No recollection of the 1940s is complete

without mention of the heavy snowfalls early in 1947, arguably the hardest

winter of the twentieth century. Even

in suburban

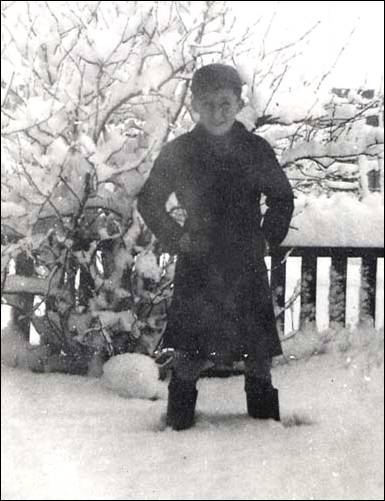

An

old-fashioned winter: Stechford Road, looking towards Hodgehill

Common

An

old-fashioned winter: Dad clears the

drive with Mom’s encouragement and I get ready to build a snowman

Sadly, we have no photographs from the 1947 winter

when snow depths made those shown above quite trivial!

Fog was another winter evil in the 1940s

and 1950s. All factories, offices,

shops and private houses burnt copious amounts of coal for heating. In still winter weather the pall of smoke

hung in the air and drifted downwards, merging with any slight mist, to cause

an impenetrable fog with visibility cut to ten or fifteen feet. It would penetrate indoors. Outside, it would paralyse traffic and even

make it difficult to find one’s way on foot.

Most traffic would cease and my father even had to walk ten miles home

from work on one occasion. We would be

led from school in a crocodile on foot, although occasionally a tram would run

through the streets, preceded by a man on foot carrying a flare to illuminate

the way. A side effect of the fog was

that the brick and stone of city buildings became blackened, and it did not do

to inspect one’s handkerchief after blowing one’s nose!

During the hard winter

of 1946-7 my school moved to larger premises, permitting a modest expansion in

numbers. The buildings were surrounded

by extensive grounds with shrubberies and winding paths, ideal for the

childhood games of hide-and-seek. Five

to eight year olds were taught in an imposing Victorian house but nine and ten

year olds were housed in a Nissen-type hut built in

the grounds for the Auxiliary Fire Service during the war. The two classes within the hut were

separated only by a pair of large hessian curtains, drawn back at play-time and

for lunch. A large coke boiler provided

the communal heat: a low railing

prevented us from coming into contact with its scalding sides and served as a

clothes horse for damp coats on wet days, thus ensuring that the hut was filled

with the objectionable smell of damp wool mingled with coke fumes. My school life in those days generally

lacked excitement;

mile-stones included the early, tentative, steps in writing and

the daily recitation of multiplication tables.

Writing at first involved using chalk on miniature slates, but later one

graduated to dip-in pens with which to practice “pot-hooks”.

This tranquil existence

suffered one brief interruption when a girl in the class complained that

another girl, called Yvonne, had stolen her fountain pen. The Principal, Miss Inshaw,

made enquiries and the pen was duly found secreted in the top of one of

Yvonne’s black woollen stockings. The

poor silly girl was expelled, causing a frisson of excitement through the

class. I had not previously encountered

the world of theft and expulsion, nor come to that, the world of stocking-tops:

sensations all, to an eight-year-old. (For more about Amberley Prep School go to

web page Amberley.)

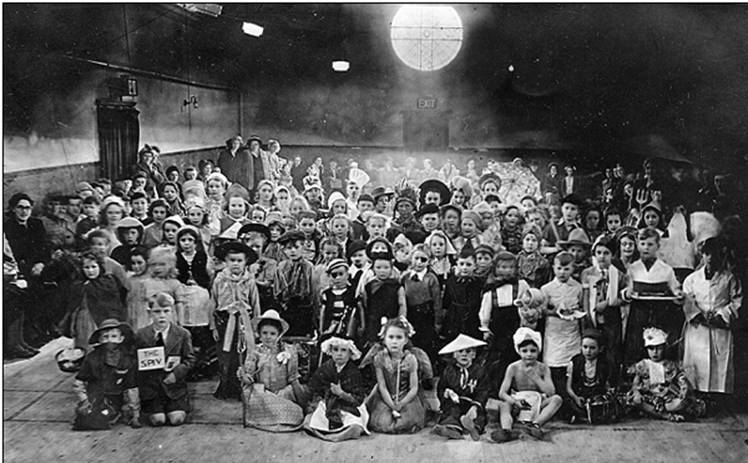

Amberley Preparatory School:

Fancy Dress competition at the Church Hall on Hodgehill

Common,

Christmas 1948 or 1949:

Manners were an essential part of one’s

education in the highly structured society of those post-war years. One did not speak until spoken to. As boys, it was impressed on us that we must

treat ladies with respect at all times, a practice still faithfully kept by

some of my generation: a gentleman

should raise his hat on meeting a lady, should hold the door open for her,

allowing her to go first, and should always stand when a lady entered a

room. On crowded ‘buses one should

always offer one’s seat to a lady.

Conversely, real ladies did not go into pubs without a male escort, nor did

they smoke cigarettes in public.

Elocution lessons ensured that we spoke correctly and avoided

colloquialisms, especially “O.K.”.

Swearing in company was almost a capital offence. One might just hear “damn” or “blast” used

under serious provocation but the words were not permitted in a child’s

vocabulary. “Bloody” was used by men

only in the most extreme situations and would certainly never have been allowed

on the wireless. Stronger language still,

nowadays common-place, was largely confined to the working man in his own

environment and would never be heard in public. Just once, a boy called Gilbert used such a

word to me. I asked my mother what it

meant, but she didn’t tell me. I was,

however, forbidden henceforth to go to Gilbert’s house, which was a pity as he

had a very good train set.

Although I had a small circle of

friends at Amberley, much of my leisure time was spent alone, contentedly

reading or playing with my Hornby Dublo

electric train set, or happily riding my blue Hercules bicycle around

the quiet suburban pavements. I am told

I learnt to read when I was three by finding Music While you Work in the Radio Times! After Rupert Annuals and Enid Blyton, I graduated to Arthur Ransome

books, ‘Bunkle’ adventures and the ‘

The

view from 165 Stechford Road:

The

view looking into Hodgehill Road dates from the early

1950, soon after the introduction of the 55 ‘bus service in October 1950, but

before replacement of the 1930s-style lamp posts by tall modern lighting. When my parents bought the house in 1932 it

faced open fields with a view to

The view of the back garden

shows the lawn around which I rode my Hercules bicycle, with the rockery beyond

(into which the air raid shelter had been built for the duration of the war)

and behind which there was a small vegetable garden.

Some leisure time

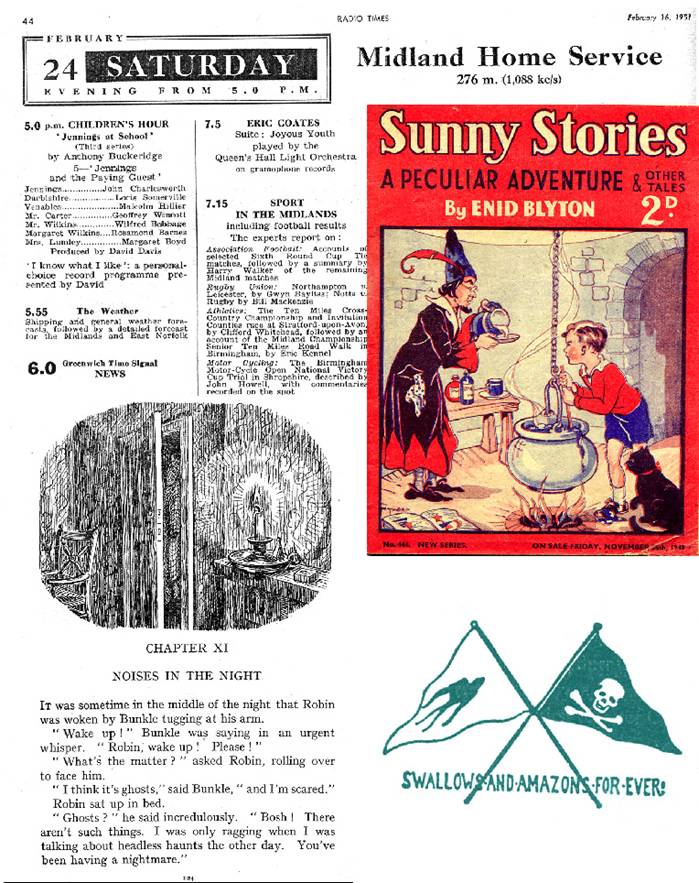

souvenirs:

Clockwise from

the top:

An excerpt from Radio Times: programmes for 24th February 1951, including Jennings at School;

the cover of Enid Blyton’s weekly Sunny Stories for November 1948;

one of Arthur Ransome’s decorations from the pages of Swallows and

Amazons;

a page from Bunkle Butts In, by M. Pardoe (1943), with

illustration by Julie Nield [The ‘Noises in the Night’ were intruders in the

secret passage!]

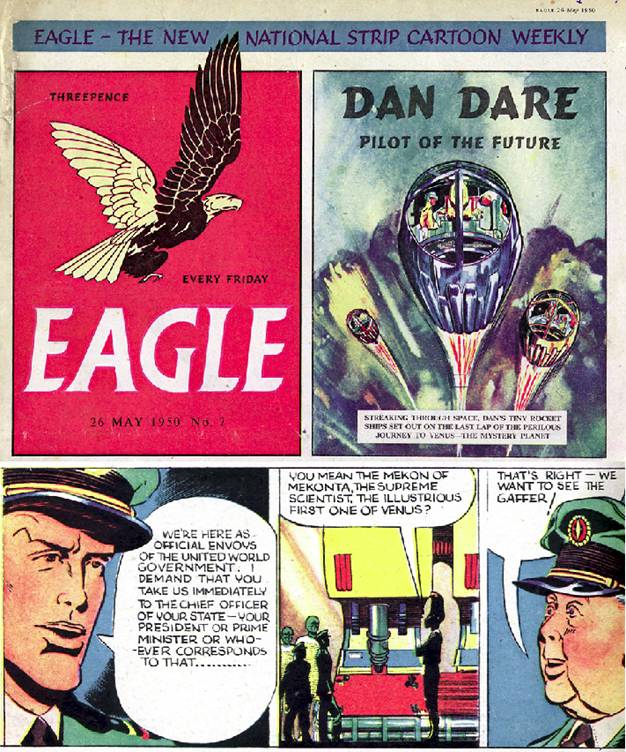

Extracts

from an early edition of Eagle, showing Dan Dare, Pilot of the Future.

Art work, by Frank Hampson,

was always of a high standard; the stories

often contained a discreet didactic element and schoolboys enjoyed the humorous

side as evidenced by the bluff Lancastrian approach of Digby,

Dan Dare’s batman.

School days (continued)

My form at school was quite small, no more than twenty pupils,

of whom most were girls. One young

friend was J’Ann Page, who moved to Somerset about

1960, but with whom I re-established contact in 1985 through a neighbour of my

parents who had remained in touch. J’Ann was a lively girl and we often enjoyed a threepenny ice cream as we walked home from the tram on the

journey back from school. But the world

is not yet ready for the curious tale of how her socks came once to be lodged

high in one of Stechford Road’s sycamore trees. In the years 1949 – 1951 two boys in

particular were my firm friends: Derek

Silk and David Yates. We tried to pass

ourselves off as a “gang”, modelled partly on Richmal

Crompton’s Just William stories and partly on

Sport scarcely featured in the

school curriculum and, although a few boys liked to kick a ball about, football

was not the obsessive interest it became in later decades. As an only child I grew up happily

uninterested in games and other competitive activities. Dad did once take me to see Aston Villa play

when I was about seven, but I was hit painfully in the face by the muddy ball

when it strayed into the crowd. This

incurred maternal displeasure, so the trip was not repeated. P.T. exercises at school took place out of

doors in fine weather only: my main

memory is that when the class was bending to touch toes I could look up to see

the row of girls in front revealing their navy blue knickers as they bent

forward. There were also swimming

lessons once each week, involving the tram ride to Woodcock Street baths. By the time one had changed – always two

boys to a cubicle! – there was time for only about

twenty minutes in the water. But

afterwards came the best bit, a cup of hot chocolate and a tiny slice of swiss roll in the café.

At ten years of age I

suffered the first pangs of interest in the opposite sex. For a while I took to eating my sandwiches

with one of the girls and we would wander around the school grounds at break

and lunchtime having earnest discussions.

I endured some taunting from “Silko” and “Yatesy” who clearly did not understand affairs of the

heart. Then, at the end of term, she

broke the news that she would be leaving and so the school “gang” member-ship

went back up to three.

Meanwhile, childish fun went on as

before. Birthday parties continued

until I was eleven. Organised by my

mother, there were games, always including “pass the parcel”, then there was

tea (actually Corona “pop” and birthday cake), and then some wild

running about in the garden until it was time to finish. Parties were always mixed, but activities

usually seemed to divide into boys v girls. The girls always wore party frocks and had

ribbons in their hair, looking as pretty as a picture: whatever happened to Myrtle Pridmore? (Late News!!

Myrtle is alive and well and living in County Durham, but Stella remains

elusive!)

Birthday

party 1951: back left: Derek Silk,

RHD, David Yates,(“the gang”)

back

right: Norma Page, Stella Richardson, Myrtle Pridmore

front:

Keith Hickinbottom, J’Ann

Page

“ Children’s Hour ”

Out of school, music was my most lasting

discovery of those early post-war years.

Ours was not a musical household and I am told that my favourite piece

of music during the war was called “Pistol Packing Momma”, long since erased from

my memory. But, like most contemporary

middle-class children, I was an avid listener to “Children’s Hour” on the BBC

Home Service (no television in those days!).

Many of the items were introduced by tuneful extracts from classical

music, some of which etched themselves permanently

into the mind. Said the Cat to the Dog opened with an extract from Walton’s Façade and “Music at Random” by Helen Henschel began with the main theme from the last movement

of Brahms’s First Symphony. One serial

used Sibelius’s En Saga. Another drew briefly on the music of

Shostakovich, and, with the help of Radio

Times, sent me on my first voyage of discovery to the newly-developed Third

Programme. (I remember, however, being

seriously bewildered by the music encountered there – not for the last

time!) At Christmas 1948 I first heard

John Masefield’s Box of Delights with

music from Victor Hely-Hutchinson’s delightful Carol Symphony. Box of Delights was to be repeated in

1955, before being transferred to television in 1984, each time with the same

music. Coincidentally, Hely-Hutchinson was also in

There was, of course, other, more light-hearted, entertainment

to be had from the wireless (as it was then called). A favourite was Much Binding in the Marsh with Kenneth Horne, Richard Murdoch, Sam

Costa and Maurice Denham. Lying in bed

on Sunday evenings, I would hear the voice of Frankie Howerd

in Variety Bandbox drifting upstairs,

accompanied by my parents’ laughter.

The most discussed show was probably ITMA

with Tommy Handley who died so suddenly aged 57 in 1949. During and immediately after the war ITMA had been a major factor in uniting

the nation: at a time when there was no

television, and wireless programmes were confined to the BBC Light Programme

and Home Service, choice was restricted and the majority of the population

would be enjoying the activities of Handley and his crew.

Television broadcasts

had started in

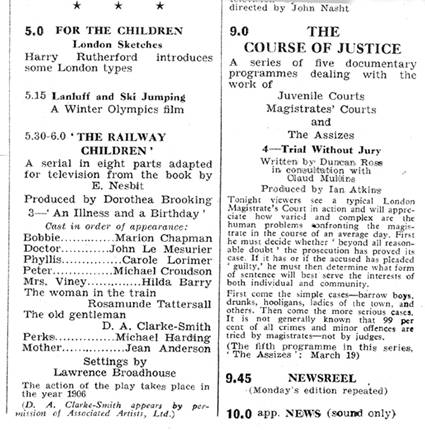

An

extract from Radio Times showing television programmes for Tuesday, February 20th

1951

After The Railway

Children the service closed down until 8.0 pm when there was a half-hour

programme about Treasures of the Victoria and Albert Museum, followed by a

French film about Montmartre. Following

the News (sound only) television closed down at 10.15 pm.

Evening programmes were

introduced by announcers dressed formally in evening wear: viewers were greeted by Sylvia Peters or Mary

Malcolm in elegant dresses and McDonald Hobley or

Leslie Mitchell immaculate in dinner jackets.

As programmes were broadcast live (even the Thursday repeat of the

Sunday night play was a second live performance) it meant that disasters great

and small reached the home screen. Not

infrequently the screen would go momentarily blank before an elegantly written

notice appeared:

“Normal Service

will be Resumed

as soon as Possible”

The first person I ever

saw drunk was Dr Glyn Daniel on the television programme Animal Vegetable and Mineral – he and his guests had evidently been

celebrating before hand, rather too well.

My first hint that sex appeal might be of some significance came about

1952 in a live programme with the elderly artist Sir Gerald Kelly talking about

(I think) Fragonard's "Girl on a Swing": he suddenly turned to the camera with a

wicked twinkle to add a daringly unscripted remark: "Look at that lovely little

bottom". My mother laughed, then

remembered I was there and said "Well!!" in a certain tone of voice.

The death of

radio’s Tommy Handley was an uncomfortable reminder of human mortality. During

the 1940s two neighbours died, comparatively young, raising in a child’s mind

the question of our ultimate destination.

The mother of Juliet Powell, a little girl with whom I sometimes played,

died in her 30s from breast cancer, and “Uncle” Bill, our next-door neighbour

died from pneumonia in his mid-fifties.

These events raised uncomfortable questions, but children look ahead,

not back, and the events were soon all but forgotten. The equally great mystery of birth surfaced

from time to time: I remember asking my

mother where I had come from, but I cannot now recall her reply which was

doubtless a masterpiece of dissembling!

But I was temporarily satisfied, without the destruction of childish

innocence which now seems to be the rule.

Much of my knowledge of

life’s caprices came from unintentional eavesdropping on my mother’s

conversations with her friends. She led

a life ordered by routine: Mondays were

for washing (morning) and ironing (afternoon), Tuesday and Friday mornings were

for local shopping, Wednesday and Thursday mornings were for cleaning –

downstairs and upstairs, respectively. Except on Monday, after an early light lunch she would change into

a smart day dress. The afternoon

was then

available for seeing friends, equally elegantly attired in smart frocks, or for

an occasional trip to the centre of Birmingham. There she would shop for clothes (although

that was limited because of the need for clothing coupons), or perhaps take me

to a matinee at the cinema. When her friends

came for tea I would often sit quietly reading in a chair in the bay window

while the ladies sat talking by the fire.

Perhaps I was invisible, because I would hear remarks about life,

husbands and acquaintances which were surely not intended for me! There was probably nothing slanderous, but I

do remember being amused by mimicry of a local lady with an affected way of

speaking who was quoted as saying “My de-ah, it took me two aahs

to arrange the flaahs.” [Two

hours to arrange the flowers.] I

felt uncomfortable (and still do) on hearing a woman complain about her

husband’s alleged domestic inadequacies.

I have never heard a man complain about his wife, suggesting that

‘cattiness’ is indeed a female attribute!

In the 1940s the two sexes lived quite separate lives: it seemed men went off to kill or be killed

fighting wars or, if living at home, set off, trilby-hatted

to work from 7.30 am to 6 pm each day.

On Saturday afternoons they went flat-capped to football, and spent any

remaining spare time caked in mud from digging the garden or covered in oil

after overhauling the car (which probably entailed lifting out the

engine). Women shopped occasionally,

cleaned from time to time, dead-headed the roses and spent the rest of their

time reading to their children or drinking tea with friends: it seemed to me an enviable existence

compared with their husbands – but things for me turned out differently and I

have no cause for complaint!

with Dad on board the

and with Mom at Tenby

after a boat trip to

Life continued with its usual minor twists

and turns. In the late 1940s I

experienced an encounter with the constabulary which was to make a lasting

change in my life – although happily without any charges being brought! During the course of a visit to the family

in

When it came to food there was no

opportunity to indulge in the whims and caprices of taste. Rationing and shortages continued well into the

1950s and many popular items were simply unobtainable. One had what one was given or went

without. Imports of bananas were

discontinued throughout the war and oranges were available only in very limited

quantities. I recall my first post-war

banana as a serious disappointment: I

think I was expecting a bigger, sweeter, more luscious orange. Domestic freezers and refrigerators were

almost unknown, so frozen foods were simply not available until limited

quantities of ice cream began to appear once the war was over: at first in vanilla flavour only; wafers three-pence,

cornets fourpence, tubs sixpence!

Dinner menus were

limited in range. Beef, mutton and pork

were the staples; lamb

was seasonal and chicken a luxury for Christmas only. Cod,

tripe, hearts and brains appeared occasionally. Meat was accompanied by fresh vegetables

according to season – my diet of green vegetables was limited mainly to fresh

peas out of the garden in July, runner beans in August and cabbage for the rest

of the year, varied only by occasional carrots or cauliflower. Tinned peas were available, but were not

especially palatable. In an era of

shortages, leftovers were recycled so that yesterday’s meat reappeared as

rissoles, vegetables as “bubble-and-squeak”, and an unwanted tea might

re-appear as bread-and-butter pudding.

Cheese was rationed to two ounces (of non-descript Cheddar) per person

per week. Eggs were scarce, but dried

egg was available for cooking and could even be made into a sort of omelette,

though my mother looked down her nose at such contrived dishes. She baked her own cakes; otherwise we would

probably have gone without. The season

for locally grown fruits was extended by careful storage of cooking apples,

giving the spare bedroom a characteristic smell, and my mother would be busy

bottling plums and damsons in Kilner jars at the end of each summer. Imported tinned fruit was unknown and I did

not taste any until a rare tin of pineapple chunks, hoarded from before the

war, was produced at a family party, held at my

father’s old home in Erdington, for Uncle Cyril who was on leave from the

Army. Foreign dishes such as pizza,

lasagne, or paella were quite unheard of; indeed, in an era when foreign

holidays were almost unknown our family would not have recognised the

words! By comparison with present-day

menus it seems a poverty-stricken up-bringing.

But the choice was planned in response to government dietary advice and

ensured a generally healthy population.

There was no chance of over-indulgence, so my friends were a skinny and

active lot, obese children being unknown!

Sweets were taken off the ration on 24th April 1949

(remembered as being my play-mate J’Ann’s birthday),

but before I could get to the corner shop for a quarter of Barker and Dobson’s

Barley Sugar or of Wilkinson’s Liquorice Allsorts panic buying by the public

had cleared the shelves nation-wide.

This resulted in the government re-imposing rationing for three more

years, frustrating the dreams of many children who were thus strictly limited

to one or two sweets a day. But in

compensation there was Christian Kunzle’s restaurant

in Union Street with its delicious Swiss-style cream cakes rich with cream

inside a chocolate ‘boat’: one greedily

eyed a plateful but could seldom manage more than one! How strange that such indulgent fare has

long since vanished from the shops!

Food rationing continued with full

severity for six or seven years after the war.

The system demanded that one was registered for food with a specific

shop. Making purchases elsewhere was

not permitted. We patronised Ehret’s, a small grocer (with a surprisingly Germanic name

for those days). There, my mother’s

order was taken over a long counter with a chair placed alongside for the

customer to rest her legs. Many items,

such as butter and sugar were parcelled up on the premises and biscuits

(plain; no cream varieties) were sold

loose from large biscuit tins, pre-packed goods being almost unknown. My mother’s purchases would be delivered

later by bicycle. I always wanted her

to call in at the Co-op, despite not being registered there, as the Co-op had a

curious aerial ropeway by which the cash was sent by the shop assistant to the

lady cashier who returned any change by the same means. (The Midland Educational book shop in

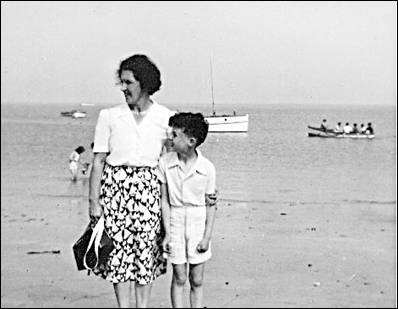

An aerial view of the

Fox and Goose shopping area, about 1949, from the pages of the Birmingham

Weekly Post.

In the left foreground is the Washwood Heath Road with trams on their reserved

track. Alum Rock Road merges in the

right foreground. The Beaufort Cinema

is just above and right of the traffic island.

The Outer Circle route crosses from left to right and Coleshill Road continues into the

distance toward Hodgehill Common, just visible where Coleshill Road bends left into the trees. The sand quarry is visible right of

centre: it was later filled in and became

Stechford Hall Park.

Rural Castle Bromwich stretches across the top of the photograph: Shard End was still just a planner’s dream.

In the late 1940s our

rations were slightly supplemented – unofficially - with the help of Aunty Rene,

a cousin of my mother’s who, like her, had left South Wales and settled in

Warwickshire. She and her husband ran

the village shop at Broadwell, near Southam and about twice a year we visited her, returning

laden with contraband packets of Weetabix, bags of

sugar, slices of fresh ham and pats of butter.

Broadwell was then a tiny isolated village

lying in a hollow, populated mainly by agricultural labourers who lived near

the poverty line. Most houses were

down-at-heel and there was an overwhelming and unpleasant smell which offended

the nostrils as soon as we got out of the car.

Explained by my mother as “stagnant water”, I later discovered the smell

was that of the village’s cesspits. On

our visits I often played with Margaret, Aunty Rene’s granddaughter and my

second cousin once removed. She was a

tall, lively girl, only a little younger than me. But in her twenties she suddenly suffered a

brain haemorrhage and died, leaving two tiny children. Aunty Rene herself died in 1960 and thereafter

we had no reason to return to Broadwell. But in 1990 I was driving nearby and decided

to make the detour to see how the village had changed. In thirty years the down-at-heel cottages

had been transformed into “desirable executive commuter homes”, each with a BMW

or Mercedes outside. The old shop was

no more, but was now the largest and most impressive of all the houses. I might add that the air was sweet and of

the smell there was no evidence.

Petrol was still rationed well into

the 1950s, so outings by car were strictly limited. On a couple of occasions, when my mother

evidently wanted an afternoon to herself, she would pack me off on the Outer

Circle ‘bus for the two hour circumnavigation of

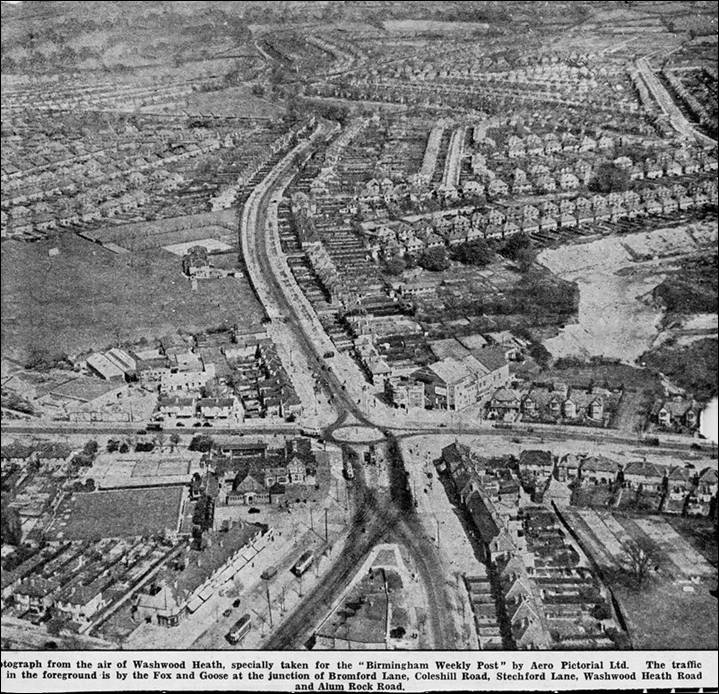

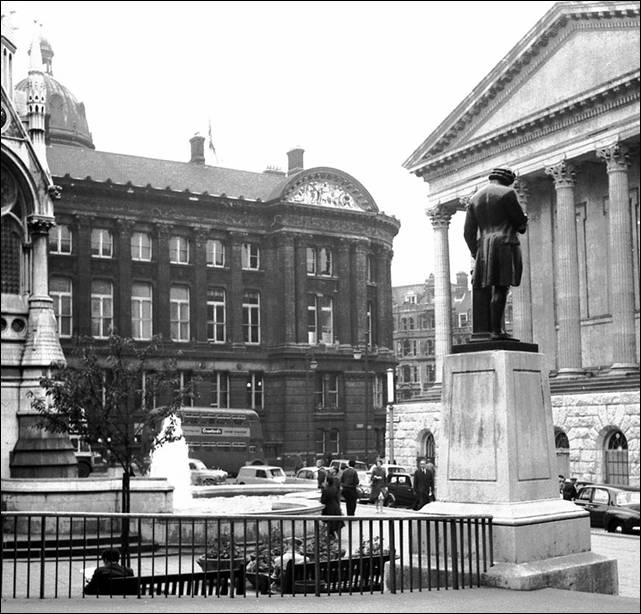

Chamberlain Place,

Birmingham:

A

The

Most stone buildings

were then blackened by the smoke in winter fogs. As atmospheric pollution diminished in the

1950s the buildings were cleaned, revealing that the stone had a natural light

colour - much to the surprise of my generation!

The King passes by

In the late 1940s and 1950s the British

Industries Fair (“BIF”) was held each year at Castle Bromwich, only a mile from

home. I was taken there on several

occasions, even though the displays of heavy engineering which were the

essential feature of the show were hardly riveting stuff, either for me or for

my mother. But there was usually an

exhibit featuring a small gauge industrial railway, intended for use in

quarries or on building sites and the promoters were generally more than happy

to demonstrate its cargo carrying capacity with a load of small boys instead of

the more usual tonnage of granite. In

1947 the BIF was officially opened by H.M. King George VI, and after the

ceremony he was taken by motorcade to join the Royal Train at Stechford station, so passing our house. This was an occasion when we watched from

our front garden as the King drove past – I was surprised to find that there

were other, lesser, mortals whose front gardens were not thus honoured by His

Majesty. I will add here, although it

belongs to a slightly later stage of my life, that in 1956 the Russian leaders,

Khrushchev and Bulganin likewise were driven past our house when returning to

catch their train to

1950: 10th birthday

For the most part, news in the

1940s passed me by, but from conversations overheard between adults, from

wireless news bulletins and occasional newspaper headlines, I gained some vague

impression of the drift of events. In

1945 I knew from the VE celebrations that the end of the war with

It now comes as a surprise

(even to those of us who were there at the time) to be reminded how innocent

and ignorant children in the 1940s and 1950s were about matters relating to

sex. Parents and schools shyly dodged

the issue. Newspapers, magazines and

the broadcast media never mentioned the topic.

Nudity was quite unknown, save for discreetly-posed black and white

pictures in a few “pin-up” magazines which were not widely available and

certainly unknown to me. Boys and girls

could thus grow up in a state of blissful ignorance of the change adolescence

would bring: nothing was said. My own innocence was signally disturbed by a

19-year-old Italian film actress, Silvana Mangano who appeared in an Italian film, Bitter Rice, released in

Silvana Mangano in Bitter Rice, 1949.

She appeared in several more films, of

which the best known

was Death in Venice in

1971. She died in 1987.

This was

the photograph which caught my eye in the Daily

Mail in 1950.

In 1951 I passed the “eleven-plus” examination for King

Edward’s School, Aston, but was also entered for the separate examination for

the ‘parent’ King Edward’s School in Edgbaston. This was a tougher proposition but I passed

and so the lengthy cross-city journey would be part of my life from

September. I would notice a change: Amberley was a tiny, informal affair, run by

a handful of local ladies, of whom Mrs Bunker and J’Ann’s

mother, Mrs Page, were my usual teachers, aided by Mrs Woodwiss

who taught History and Geography on Thursdays and Fridays only. For a couple of terms, there was a small

sensation when they were joined by a man, Mr Luby.

At Amberley I was a big fish in a very small pool, but at King Edward’s I would find myself a very small fish indeed. The culture shock would be significant. Instead of the company of a small number of girls and an even smaller number of boys, there would be 700 pupils, many already grown men over six feet tall. Although girls continued to use their Christian names in secondary education, boys were always known just by their surnames. To call a fellow pupil by his Christian name would be seen as excessive familiarity, so even when visiting a school friend at home, he, his mother and his sisters would all address me as “Darlaston”. Life at King Edward’s would bring testing new subjects including Algebra and Latin to puzzle my mind, and games such as rugger (about which I knew nothing) followed by showers or the muddy communal bath where I would quickly abandon the modesty learnt in my childhood. But this new existence would soon cease to be strange and would itself become second nature.

The early ‘fifties were marked by

three events of national significance:

the Festival of Britain in the summer of 1951, the death of H.M. King

George VI in February 1952, and the Coronation of our present Queen in June

1953. These printed themselves on my

memory in different ways. I remember

the Festival firstly for the journey up to

The death of the King was, to a

child, quite unexpected, the news reaching my form as we waited to go into the

school dining hall. After the colour

and fun of the previous year’s festival, the state funeral itself had an

overwhelming and numbing sombreness, awe-inspiring even to an

eleven-year-old. Monochromes dominated

everything, not just on the tiny black and white television, but in the whole

of that cold, grey, austere February world.

Gaiety returned the next year in time for the Coronation, even

if the weather itself famously failed to co-operate on the day. But

with hindsight, I now realise that in watching the splendid spectacle of

Coronation Day I was witnessing the finale of the British Empire and of the Pax Britannica; the world of my parents and of my

grandparents; the world of my own

childhood; the world I had been brought

up to believe was Great Britain’s gift to all mankind for eternity.

* * * * *

In Retrospect

The early 1940s was a surprisingly good time in which to

be born. I was too young to be much concerned

either by the war or by the privations which continued for some years

afterwards. I saw and experienced a

world which still depended on horse power and the steam engine, when country

life was little changed from that which had obtained centuries earlier. But I was born in time to enjoy the

increasing material prosperity of the 1950s and early 1960s, while still having

the old-fashioned freedom to explore my surroundings free from the fears of

crime and violence which affect today’s children. I was in time to benefit from the general

availability of a wider and more attractive diet, and also of improved

medicine, especially antibiotics and better anaesthetics.

The full employment of the post-war era meant it was easy

to get a well paid and interesting job with security and also with prospects

which were duly realised. Those who

were born in later decades were not to find employment so easy, and, for many

of the rising generation, the outlook for early retirement and a generous

pension is much less promising than for my generation.

It is easy and commonplace for my

generation to think back to our childhood days and to lament the loss of

innocence. We are now immersed in a

depressing climate of violence, of aggression and confrontation, of tasteless

and sometimes offensive talk, evident in everyday life, in the press and

especially on television. There are

manifold petty restrictions and the absurdity of “political correctness” which

limit once cherished freedoms. But

against that one must set the improved living standards, especially health

care, and such material benefits as cars and computers, refrigerators and

televisions, central heating and air conditioning; plus the travel and holiday opportunities we

now accept as commonplace.

I may have enjoyed myself in the

1940s and 1950s, but I would not go back:

there is so much in life to enjoy today!

Robert

Darlaston, November

2008

Some minor alterations, April 2018

robertdarlaston@btinternet . com

(For anti-spam purposes, this is not a

link: please retype direct into the

address box omitting spaces)

Links:

You might also be interested in the

following further pages, all with many photographs:

Family

Photos.htm (A gallery of photos of family life from the 1940s to date)

FamilyTrees.htm

(Family history, including tentative links back to 1373, in the reign of King

Edward III !)

Amberley.htm (More memories and memorabilia of life at

Amberley prep School, 1945-51)

KingEdwardsSchool.htm (Life at King Edward’s School, Birmingham, in

the 1950s.)

Birmingham

Pictorial.htm (Photographs of

Birmingham in the first decade of the 21st century)

If other pages are not listed to the left, our

Home Page can be accessed here: www.robertdarlaston.co.uk

POST

SCRIPT

The pages above describe my

life until the early 1950s. The rest of

that decade is described separately in my memories of life at King Edward’s

School, and the subsequent years of office life are mentioned in my separate

account of my time in banking. But

there is more to the story:

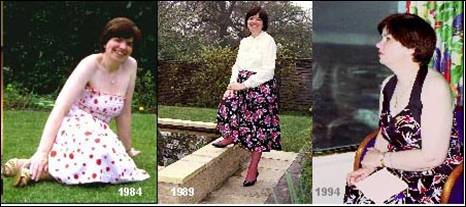

Barbara

through the years

Barbara came

into my life on Monday, 25th January 1965, when she joined the staff

where I worked in Colmore Row,

How quickly

those years have passed! One looks back

on a kind of internal photograph album as different events spring to mind: our earliest trips to concerts in Birmingham

Town Hall, to films at the Scala Cinema and to some

strange plays at Birmingham Repertory Theatre – a melange of Beethoven, Robert

Bolt, Shakespeare and Joe Orton served up respectively by Sir Adrian Boult, Paul Schofield, Richard Chamberlain and Mike Gambon. Then there

was our membership of the Handsworth Wood Gramophone Society, our two holidays

in Cornwall (the first when we were engaged, daringly unchaperoned

– but boringly proper!), visits to the family in South Wales and our first trip

abroad, to Switzerland, travelling out on the Rheingold Express up the Rhine

Valley, trips up the Jungfrau, across to Montreux and

down into Northern Italy, eventually returning via Paris and the Night Ferry to

Victoria.

Our stay in

Home, Sweet Home! Our houses:

Four Oaks (2nd house from left): June

1972–February 1973; Thurston, Suffolk:

February 1973–May 1974; Cheshire:

from May 1974

If other

pages are not listed to the left, our Home Page can be accessed here: www.robertdarlaston.co.uk

E-mail address: robertdarlaston@btinternet . com

(For anti-spam purposes, this is not a link: please retype direct into the address box

omitting spaces)